Filmmakers

Films That Changed The World: Philadelphia (1993)

For it’s 1993 release, the Jonathan Demme film, Philadelphia, set a novel precedent. At this time, the HIV/AIDS virus was essentially a death sentence for the estimated 2.5 million people diagnosed. These dying individuals became pariahs, since many powerful political figures, including North Carolina Senator Jesse Helms, openly believed that AIDS victims deserved to suffer in silence for their “incredibly offensive and revolting conduct” (The New York Times). Furthermore, Roman Catholic cardinals had condemned the so-called “gay plague” as a “disease of the sinful,” and it became increasingly common for “health care providers [to] refuse to provide [LGBT individuals] needed care because of personal or religious beliefs” (National Women’s Law Center).

As a result of its stigmatization, misinformation and fear regarding the contagiousness of the AIDS virus ran rampant throughout the United States. After an agonizing 12 years of panic and exasperation since the onset of the deadly outbreak, Philadelphia was the first major motion picture to ever actually address the widespread issues of HIV/AIDS, homophobia, and discrimination. The film was nominated for the Best Original Screenplay Academy Award and claimed two Oscars for Best Actor, Tom Hanks, and Best Original Song, by Bruce Springsteen. It has since received praise for having initiated and “changed the national conversation about the disease” (Columbia University).

The film itself revolves around the character of Andrew Beckett (Tom Hanks), an exceptionally successful lawyer at the largest corporate law firm in Philadelphia. That is, only whilst his employers remain unaware of his sexual orientation and AIDS diagnosis. In a disturbing turn of events, Andrew is suddenly fired from the firm, due to what he believes is blatant AIDS discrimination, as he can no longer hide the telltale Kaposi’s Sarcoma lesions on his face. Now, desperate for an attorney to take his case, he is forced to procure the services of the homophobic, ambulance-chasing Joe Miller (Denzel Washington). However, as Joe begins to form a relationship with Andy and his gay partner, Miguel Álvarez, he gradually overcomes his own prejudice and gains insight to the terrifying, everyday struggle of innumerable AIDS victims. Joe proceeds to win the court battle for Andy, who succumbs to the fatal disease shortly after testifying.

Besides its foreseeable plot, the film is smartly strategic in many ways. For instance, Jonathan Demme, fresh off his Best Picture win for The Silence of the Lambs, was very intentionally chosen as the celebrity name to direct the controversial motion picture. Because Demme intended to “reach the people who couldn’t care less about people with AIDS,” Tom Hanks, “a very likeable heterosexual actor,” was specifically cast as the empathetic face of the tragic disease. Philadelphia’s successful, “paint-by-the-numbers” technique culminated in a final box office earning of $206,678,440.

As Marla Gold, HIV doctor and public health dean at Drexel says it well, “here we have a major star, playing a significant role with a visual for HIV, acted out beautifully as a movie that’s award winning. So this is a lot different than a pamphlet that arrives in the mail and warns you of something. This is real” (NewsWorks). By utilizing cast and crew that were familiar and positively received by Middle America, the film gained enough credibility to transcend the heavy stigma associated with media coverage of the so-called “gay plague.” The film also more directly impacted LGBTQ individuals, since many AIDS victims themselves were cast as extras, giving them an opportunity to work after many had lost their jobs or faced difficulties obtaining one due to their illness.

Despite this, the film also received its share of criticism, and Hanks himself contends that “the volatile reaction, so overwhelmingly negative in some cases, brought the subject matter to the forefront in a better way than the movie could have ever done” (The Independent). This controversy was predominantly sparked by the review of LGBT rights activist and founder of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP), Larry Kramer, harshly entitled “Why I Hated Philadelphia.” His frustration is mostly attributed to the film’s lack of any real stance on the political issue of AIDS treatment/funding, and the fact that Andrew and his partner’s interactions are not representative of typical homosexual relationships. The film is surprisingly conservative in this aspect, as there is a near absence of any on-screen romance between the couple. In fact, the only scene of Andy and Miguel in bed together was ultimately cut from the final version of the movie. Additionally, the film’s creators have been castigated for misappropriating the factual stories of AIDS discrimination towards both the late Clarence Cain and Geoffrey Bowers. In Bowers’ case this even resulted in a winning lawsuit against the film’s production company, TriStar Pictures.

As a self-identified queer filmmaker, the issue of LGBTQ representation in cinema is especially dear to me. While there’s no doubt that Philadelphia precipitated change, it’s important to note that a film does not require a necessarily positive impact to be considered historically influential. With that being said, my heart wanted so much to agree absolutely with Kramer’s critical words. Purposeful misrepresentation in cinema, especially of historically oppressed individuals, is ethically inadmissible for its perpetuation of falsities and entertainment of problematically distorted realities.

While I concur that in many ways the film “doesn’t bear any truthful resemblance to the life, world and universe I live in,” I seriously do not think a 1993 America would have accepted the raw and honest depiction of gay couples that Kramer advocates for. In a world where, as Kramer himself states, “AIDS is happening to certain communities others would just as soon see dead,” it is simply too idealistic to venture that these same “others” would voluntarily see a film that not only challenges their homophobic notions, but does so in a way that approaches the threateningly taboo topic of gay sexual acts. I can only fathom that if there had been a single sex scene in Philadelphia, the film itself would never have even made it to theaters.

In this instance, given Demme’s intended audience, I think that it is justified to prioritize the destigmatization of the gay community through Hank’s “everyman” character over proper representation of it. As much as it discomfits me to say so, I believe that this strategy is the main reason why Philadelphia was incredibly effective for its time. While it may not be the most righteous piece of cinema for this reason, I think its impact was felt so heavily precisely because the same individuals who feared catching the “gay plague” from shaking hands, or a public toilet seat (which is physiologically impossible, by the way), actually paid money to see a film that, albeit very gently, told them exactly why their prejudices were unfounded.

At least in comparison to Demme’s previous film, The Silence of the Lambs, which was decried by the gay community as homophobic and transphobic, Philadelphia represents slow progress. After all, the mere the existence of this conservative film allowed for the gradual proliferation and eventual praise of academy award-winning, sex-positive films like Brokeback Mountain (which, even in 2006, was pulled from theaters in Utah for its homosexual content).

Undeniably, the impact of Demme’s film was extremely significant in initiating, on a larger scale, the conversation about AIDS that much of America had no desire of entertaining. Even to this day, more than 5,700 people will contract HIV every 24 hours, and, while the LGBTQ community continues face oppression in many forms, we can be thankful that, due to the production of films such as Philadelphia, considerable progress has been made in regards to these issues over the past 20 years.

Further Reading/Viewing:

- The Normal Heart (2014)

- How to Survive a Plague (2012)

- The Celluloid Closet (1995)

- “Discrimination and homophobia fuel the HIV epidemic in gay and bisexual men” by Perry N. Halkitis, PhD, MS

- “Health Care Refusals Harm Patients: The Threat to LGBT People and Individuals Living with HIV/AIDS” by National Women’s Law Center

- “Sin, Sex and Science: The HIV/AIDS Crisis” by Michigan State University

- “Vindicating a Lawyer With AIDS, Years Too Late” by Mireya Navarro

- “What Is the Story Behind the ‘Philadelphia’ Story?” by Terry Pristin

- “Why I Hated Philadelphia” by Larry Kramer

Filmmakers

Out of the Basement: The Social Impact of ‘Parasite’

When Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite won multiple Oscars at this past weekend’s 92nd Academy Awards, the reaction was one of almost unanimous joy from the attendees and much of the American audience. Setting aside the remarkable achievement of a South Korean movie being the first to win Best Picture, this was due to the fact that so many people have been able to identify with Bong’s film, engaging in its central metaphor(s) in their own individual ways. Everyone from public school students to Chrissy Teigen have expressed their affection for the film on social media, proving that the movie has reached an impressively broad audience. The irony of these reactions is noting how each viewer sees themselves in the film without critique—those public school students find nothing wrong with the extreme lengths the movie’s poor family goes to, and wealthy celebrities praise the movie one minute while blithely discussing their personal excesses the next. Parasite is a film about class with a capital “C,” not a polemic but an honest and unflinching satire that targets everyone trapped within the bonds of capitalism.

Part of Parasite’s cleverness in its social commentary is how it depicts each class in such a way as to support the viewer’s inherent biases. If you’re in the middle-to-lower classes, you find the Kim’s crafty and charming, and echo their critiques of the Park’s obscene wealth and ignorance. If you’re a part of the upper class, you empathize with the Park’s juggling of responsibilities while indulging in their wealth, and have a natural suspicion toward (if not revulsion of) the poor. If you have a foot in both worlds, like housekeeper Moon-gwang and her husband Geun-sae, you can understand how the two of them wish to not upset the balance, so that they can secretly and quietly profit. All throughout Parasite, there’s a point of view to lock onto.

The point of the film is not to single out one of these groups as villainous, but to show how they’re part of a system that is the true source of evil. The movie has been criticized for lacking a person (or persons) to easily blame, which would of course be more comforting dramatically. Bong (along with co-writer Han Jin-won) instead makes the invisible systems of class and capitalism the true culprit, which is seen most prominently at the end of the film. All the characters are present at the same party, whether as hosts, guests, help, or uninvited crashers, and each class group suffers a mortal loss. It’s all part of the tension built throughout the movie coming to a head, yet there’s an inevitability to these deaths as well, a price each group inadvertently pays to keep the corrupt system they’re all a part of running. In this fashion, the movie is reminiscent of several works of dystopian fiction, such as Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery,” and Aldous Huxley’s “Brave New World.” The film particularly recalls Ursula K. Le Guin’s short story “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas,” in which a utopian society is dependent on the continual torture and misery of a single child. Every system demands sacrifice, and Bong and Han make clear that that sacrifice is paid many times over.

The real twist of the knife in Parasite is the epilogue, which reveals that the real point of the class and capitalist systems is to keep as many people in their place as possible. The Park’s remain wealthy, and easily move away from their old house. The Kim’s remain in their same squalid hovel, with their patriarch now stuck in the basement hideaway of the Park’s old home. In “Omelas,” the tortured child is kept in a basement, as well, and where that story tells of individuals who reject that system and choose to leave it, Parasite shows that everyone has chosen to stay, with the erroneous belief that they can eventually change their place. The film’s intense relatability is likely the main reason for it being so beloved, yet it’s the messages it sneaks in that will hopefully be its most lasting social impact. All of us are still trapped within the system, but at least the secret of how it fails us and how it lies has managed to escape the basement. Let’s hope we can eventually escape, too.

Filmmakers

What are the challenges of filming a foreign culture?

Filming a foreign culture is not like filming your own. There are a lot of challenges that are faced by people to film a foreign culture. One of the basic reasons is that you may not know much about that culture, which will act as a drawback when trying to accurately record it. It is not about the niche of the location, but the reality of it and where that takes us. When you film culture, you must have a great understanding of it. Therefore, you should study it to get a good understanding of the nuances of the culture.

Films have a huge impact on other societies, and if your film lacks the essence of the culture, it won’t be able to give a good impression to your viewers. A lot of people get overwhelmed by other cultures and their uniqueness, most of the times getting an idea about other cultures through film, television, and the internet. Be it culture or any other information, filming has played a huge role in cultivating an impression on the minds and hearts of the people.

Filming Foreign Cultures – A Challenge

Filming in foreign countries is difficult because penetrating deep into the society of any country and culture requires a good understanding of the subject. Having that understanding can alleviate these hurdles.

Seeing the Foreign Culture Through the Eyes of the Camera

Most of us get the an idea of foreign cultures from media representations, this is because we cannot experiences all the worlds cultures for ourselves. That’s why people use social media and other internet platforms to learn about different cultures around the world. That is why whatever you make, people will see, and start believing. Which is why there is a huge responsibility to show different cultures accurately.

Challenges Faced During Filming

When you take ownership of showing the world different foreign cultures, you must make sure that everything is authentic. Made up stories won’t do because they will have a bad impact on the culture but also your credibility. That is why you should try to keep things real and accurate.

Originality

Keeping everything in its original state is the best thing video maker can do. Uniqueness and creativity are acceptable, but when the things start getting faux, the real essence gets lost, which is why it’s important preserve things in their original form.

Money and Finances

For film shooting in foreign countries, a lot of money and financial aids are required. Very good artists don’t get the opportunity to use their abilities because they don’t have enough money to film. For productive and creative filmmaking you need money, if that’s not there the problems are obvious.

Video Making on Demand

If there is a demand for a particular story, everyone will try to make videos on that subject. Sometimes, in these cases, the real story gets hidden. Many times, people do not film what is needed because they re too busy filming what is trending. This affects the film industry and the filmmakers as well.

Lack of Creativity

Lack of creativity is no doubt a huge challenge for the film making industry. Sequels and remakes of the videos are not something in demand and that demeans the meaning of creativity. If you want to make a statement, you must show how creative you are. This will help you get to the limelight in no time.

The film industry is progressing at a very fast pace and with great power comes huge responsibility, that’s what we all need to understand. Admit the fact that what you portray will be saved forever, and that slight irresponsibility can ruin another culture, which should not be the intention of anyone.

This article was written by William Roy, check out his website Movie Trivia

Academia

What is USC’ Media Institute for Social Change?

The Media Institute for Social Change, known as MISC, is a production and research institute at the USC School of Cinematic Arts focused on using media as a tool for effecting social change. Founded in 2013 by Michael Taylor, a producer and Professor in the School’s famed Film & Television Production Division, the MISC maxim is that “entertainment can change the world.” It spreads this message by producing illustrative content, and by mentoring student projects, awarding scholarships and leading research. “We are training the next generation of filmmakers to weave social issues into their films, television shows and video games,” says Taylor. “As creators the work we do has a huge impact on our culture and that gives us an opportunity to influence good outcomes.”

In recent years MISC has partnered with organizations including Save the Children, National Institutes of Health and Operation Gratitude, and creative companies like Giorgio Armani, the Motion Picture Association of America and FilmAid, to create groundbreaking work that have important social issues woven into the narrative. MISC also worked with USC’s Keck School of Medicine to create Big Data: Biomedicine a film that shows how crucial big data has become to creating breakthroughs in the medical world. Other MISC films include the upcoming The Interpreter, a short film centered on an Afghan interpreter who is hunted by the Taliban, and The Pamoja Project, the story of 3 Tanzanian women who determined to help their communities by immersing themselves in the worlds of microfinance, health and education. MISC has also partnered with the app KWIPPIT to create emojis that spread social messages. Together they co-hosted the Project Hope L.A. Benefit Concert to spread awareness about the massive uptick of homelessness in Los Angeles.

The Power of the PSA or How to Change the World in 30 Seconds, which documented the institute’s collaboration with the Los Angeles CBS affiliate KCAL9 to make PSAs on gun violence, internet safety, and PTSD among veterans. Another MISC-sponsored film, Lalo’s House, was shot in Haiti with the intention of exposing the child trafficking that is rampant there and in other countries, including the United States. The short film (which is being made into a feature) was used by UNICEF to encourage stricter legislation prohibiting the exploitation of minors, and has won several awards, including a Student Academy Award.

“Our goal,” says Taylor, “is to send our students into the industry with the skills and desire to make entertainment that has positive impact on our culture.” The dream is a variety of mass-media entertainment where social messages aren’t an afterthought but are central to the storytelling.

For more about MISC and its projects, go to uscmisc.org.

-

SIE Magazine9 years ago

SIE Magazine9 years agoWhat Makes A Masterpiece and Blockbuster Work?

-

Companies6 years ago

Companies6 years agoSocial Impact Filmmaking: The How-To

-

Media Impact5 years ago

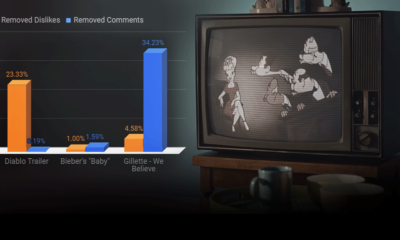

Media Impact5 years agoCan We Believe The Gillette Ad?

-

SIE Magazine9 years ago

SIE Magazine9 years agoDie Welle and Lesson Plan: A Story Told Two Ways

-

Academia8 years ago

Academia8 years agoFilmmaking Pitfalls in Deal-Making and Distribution

-

Academia8 years ago

Academia8 years agoJoshua Oppenheimer: Why Filmmakers Shouldn’t Chase Impact

-

Filmmakers9 years ago

Filmmakers9 years agoStephen Hawking vs The Elephant Man

-

Academia9 years ago

Academia9 years agoIMAX Documentaries: Exploring Our 7th Sense