Academia

IMAX Documentaries: Exploring Our 7th Sense

For audiences nearly a century ago, magic was believed to play an integral part in the production of filmmaking. Filmmakers were like magicians, discovering new techniques to fool its viewers into believing the unbelievable, and causing them to jump at films like Arrival of the Train (Lumière, 1895). However, film brought more than illusion; it was the first medium to capture life as it unfolds in real time. A film like Nanook of the North (Flaherty, 1922) was the first of its kind to utilize filmic technology to capture the unknown and deliver it to the industrial world. In this article I will explore how technological advances have had an impact on the progression of documentary filmmaking, focusing specifically on IMAX’s 3D technology. IMAX’s technology has introduced what I’m calling a 7th sense, a movie-going experience that’s bringing people back into theaters and reacting similarly to how they did a century ago to films like that of Lumière and Flaherty. Documentaries, as we’ll discuss, are narratives that balance between both fact and fiction; in order to explore this further, I will focus on how the IMAX format challenges or enhances the validity of documentaries given its technological advances. IMAX’s technology has become so sophisticated that the manipulation of image, as I’ll discuss, has almost become a fabrication in and of itself due to its high pixel density. Yet, its images are perceived to be so real that people today are reacting physically toward films, just as they were 100 years ago to its ‘illusions.’ To explore IMAX’s influence on a documentary’s validity, I will use John Belton’s Widescreen Cinema to discuss the history of 3D and the 70mm format to provide context as to where we are today. I will also draw from John Belton’s “Digital 3D Cinema: Digital Cinema’s missing Novelty Phase,” as well as Thomas Elsaesser’s “The ‘Return’ of 3D: On Some of the Logics and Genealogies of the Image in the Twenty-First Century” in order to discuss the effects of 3D and digital technologies to deduce how its not only revolutionizing documentary, but also generational experiences. IMAX prides itself on its unique, fully immersive format; having recently invested tens of millions of dollars in its documentaries. IMAX is hinting at a continued desire to not only continue to educate their audiences, but to also attempt to turn real life into a cinematic experience. I will conclude in answering the question of whether the IMAX format is eradicating cinema as we know it, or if IMAX is a form of cinema’s rebirth and thus creating a form of commercialized documentary; where moviegoers would actively go to a museum or multiplex to watch a documentary film for both its cerebral and cinematic experience. In exploring these complexities we will see how documentary’s mix of fact and fiction work into the IMAX format, and where this could take the future of documentaries.

Cinerama was one of the first successful commercialized theaters to display widescreen cinema to the masses. It was originally a medium for documentary travelogues, built during a time when the film industry feared cinema’s decline over television’s growing popularity and success. At Cinerama’s release, “reviewers spoke of Cinerama as if they were seeing motion pictures for the first time.”[1] Cinerama was described as having a larger-than-life experience that drew people away from their televisions and back into the theaters. As Belton describes, “Cinerama recaptured the experience of those early films and restored affective power to the motion picture… Even veteran airmen reacted to Cinerama’s illusion of reality.”[2] Cinerama, much like IMAX 3D as I’ll discuss, re-stimulated the senses in a way moviegoers had never experienced. Cinerama was not as passively consumed as narrative cinema as it allowed for its viewers to gain awareness with the screams and gasps of their fellow spectators; it was “not so much something people saw as something they did.”[3] In its 360-degree, 300 by 30 foot screen and 70mm format, Cinerama’s technology gave something to cinema that hadn’t been familiarized before.[4] Thus, Cinerama’s format created an inter-audience sense of participation, where its effect was intensified by the viewers’ reactions as well. Their expansive screen introduced a consuming experience that challenged conventional ways of projection and filmmaking, compared to the common 35mm format. Cinerama’s travelogue plots “took advantage of Americans’ increased interest in domestic sightseeing and travel abroad” post WWII, introducing a new kind of documentary that was both cerebral and a spectacle.[5] So many people were enthralled by what they saw at a Cinerama theater that it even stimulated tourism; IMAX arguably emulates this format today in the making of their transcendent nature documentaries.[6] Cinerama’s technology “constituted the most extreme instances of cinema as pure spectacle, pure sensation, pure experience.”[7] Thus, Cinerama’s innovations paved the way for IMAX’s immersive experience today that is setting the precedent for how we watch films, all of which began with documentaries.

To this day, IMAX’s original content resides in documentary filmmaking where their focus relies on nature/space narratives, perhaps knowing that stylistically, its format caters best to these genres. Elsaesser agrees scenes that “have no horizon, where characters are floating or leaping, flying or swimming seemed to work much better in 3-D than scenes with people walking or talking in shot-counter shot.”[8] Thus, IMAX’s format best utilizes the expository and even reflexive modes as their idiosyncratic technologies are best suited for shots that focus on the grandeur of nature; their 3D technology throws itself at the audience to make them aware of its intrusive nature and immersive technology in violating normative space.[9] By focusing on these characteristics, IMAX caters to what first fascinated people when film was introduced over a century ago. As Bill Nichols describes in Introduction To Documentary, documentaries originated from “cinema’s love for the surface of things, its uncanny ability to capture life as it is… of people, places and things,” a characteristic that resonates with IMAX’s documentary brand.[10]

Elsaesser discusses how modifications are made in technologies in order to produce greater effects of realism in films; documentaries over time have adopted new technologies to explore different techniques. We saw this for example in the mid 20th century with the introduction to portable cameras, which produced the “fly on the wall” technique, or what became known as “direct cinema”; similarly today, the use of GoPros now allows for a visceral, up-close experience in films like, Leviathan (Zvyagintsev, 2012) as well.[11] However Elsaesser posits that attaining realism is what drives technological advancements in film, where today 3D now sits in the driver’s seat despite critic speculation. He writes,

Much of the objective to 3-D on the part of critics and even filmmakers comes form the assumption that 3-D enhances vision and produces greater and greater realism – realism being one of the enduring, if questionable teleologies said to drive the history of the cinema and its chief technological innovations (silent to sound, black-and-white to color, 2D to 3-D).[12]

Recently IMAX introduced their latest laser projectors that shoot two projectors at once, without a glass prism (as opposed to most digital projectors that still operate using a glass prism and a single projector). Taking away the prism technology redirects “the light from a trio of lasers onto a screen in precise mixes and intensities to reproduce more colors then the human eye can discern.”[13] Still, no such technology can steer away from the documentary’s inevitable balance between fact and fiction. Given that documentaries operate through a series of shots edited together to construct the filmmaker’s point of view, there exists a bias and thus fictional element through such manipulation.[14] If IMAX’s new technology produces more colors than the human eye can process, it’s as if IMAX’s documentaries balance between fact and fiction on both a narrative and technological level. As Nichols writes, “Documentary voice… derives from the director’s attempt to translate his or her perspective on the actual historical world into audio-visual terms.”[15] However, IMAX’s technology challenges Nichols’ described voice as told by “audio-visual terms,” as it both confines and liberates directors in persuading them to shoot for the IMAX format. In other words, IMAX’s audio-visual terms can influence a director’s voice in how they decide to film in order to specifically cater towards 3D. However, if we compare this idea to direct cinema it isn’t much different to a filmmakers “fly on the wall” technique, where their audio-visual terms were also shaped by the functionality of new portable cameras thus forming new kind of documentary filmmaking. Moreover, this technological bias in filming with IMAX is what Nichols would also argue to be an “institutional framework.” [16] In this case, our framework operates within the technological bias in addition to the narrative bias; thus my interest resides in the issue regarding visual veracity given IMAX’s technology. However as Elsaesser argues, “3D is only one element resetting our idea of what an image is and, in the process is changing our sense of spatial and temporal orientation and our embodied relation to data-rich simulated environment.”[17] In combining narrative and technological biases IMAX technologies have uncovered a 7th sense in a growing technical era where it can take more than a film’s anecdote to produce external human reactions. It is in fact these perceived technological biases, given its unique format that causes viewers to be convinced of what they are seeing on screen, as it would be in person.

IMAX’s novelty resides in the fact that their documentary brand is an attempt to create a product where digital 3D will finally offer, as Belton describes, “audiences something they could not get at home or in conventional, non-digital, movie theaters.”[18] IMAX’s technology is revolutionizing the way we watch documentaries and is changing moviegoers’ generational perceptions towards cinema. It taps into a 7th sense, with the ability to change our “perceptual and sensory default values… a different awareness of bodily orientation and physical location.”[19] Wim Wenders’ film, Pina (2011), and Werner Herzog’s film, Cave of Forgotten Dreams (2010), are both examples of a director’s first serious venture into documentary; documentaries that capitalize on the transcendence of 3D.[20] Elsaesser quotes Nick James, a film critic, who evaluates these documentaries and the ambition in making them 3D specific. James says, “As a spectator, to be positioned by the camera above, beside and amid the dancers of Bausch’s Wuppertal troupe is not unlike floating bodiless through more solid phantoms” and in the case of Herzog’s film he writes,

The tremendous sense of movement in these depictions of animals depends on the curvature of the walls of the Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc caves…. Together, these [two] films suggest that 3-D might find its best uses in bringing real rather than imagined things to us.[21]

James’ critiques might seem contradictory given the digital nature of 3D and the capability to manipulate image and process; a contradiction that would lead most of us to believe such perceived manipulation would equate to fabrication. However, the validity of what is being seen in an IMAX film should be measured less on an objective, technological level and more on a subjective, emotional base that’s measured by an audience’s initial reaction. Audiences recognize something that is inherently unrealistic, like animation films and CGI effects in action movies like Gravity (Cuarón, 2013); it’s these fabrications that are losing the attention of moviegoers by creating a sense of impersonal and emotional detachment. However, the intention of 3D is to relieve that feeling in moviegoers through its advancements in technology, as opposed to its technology detaching from the real. It can take fictional movies like Gravity (Cuarón, 2013) and make them feel that much more realistic. It can more importantly take documentaries, films that deliberately try to portray the real, and get them the closest they can be to authenticity. It can immerse us in something that we know to be objectively true, like Mount Everest or NASA space aviation, and trick us in literally feeling immersed in the landscape of the movie – even if just for a moment. IMAX does this through stimulating a newfound sense that intrudes into personal space, enlarging “the scope of perceptual responses” and deepening “the affective engagement of the spectator.”[22] This kind of engagement adds to the audience’s perceived validity of the film, working in tandem with our senses thus making it feel more real. In doing so, it works in two ways that make it a spectacle to be seen, working towards “integrating the originally disruptive effects of stereoptic depth cues with other monocular depth cues, such as resolution, shading, color and size.”[23] In other words, by combining the monocular, a more simplistic form of optics that literally translates into having one eye, with stereoscopies, the concept of 3D that creates depth of vision through angling two photographs, it has the potential to enhance a film’s perceived validity in creating the realist representation that it can in a documentary. Despite the debatable factual evidence of what is being told in a narrative sense, the root of the technology’s objective is to show the footage in its realist and clearest potential.

IMAX is working towards becoming the mainstream way in which we watch films. As Belton argues much of the slow progression in integrating a technology that emulates the real comes from its lack of undergoing a “novelty phase.”[24] As Belton describes, “Digital 3D marks an attempt on the part of the film industry to artificially manufacture a novelty phase for digital cinema.”[25] In other words, it’s becoming the answer towards cinema’s rebirth and the way future generations will watch movies of all kinds. 3D continues to improve the movie-going experience through focusing on perception through all sensory organs. Thus, to answer our original question, IMAX’s format ultimately enhances the validity of a documentary film. 3D is becoming a “sensory substitution, where sound becomes a modality of seeing, making vision an appendage to hearing, with monocular sight increasingly submerged in the sea of stereo sound.”[26] To draw a comparison, IMAX and the Sensory Ethnography Lab (SEL) at Harvard are attempting to accomplish similar tasks with documentary. Our senses are becoming the point of interest in catching our attention in order for us to relate with the validity of a documentary. SEL describes their mission as “taking their subject the bodily praxis and affective fabric of human and animal existence,”[27] while IMAX similarly states it is an “experience so real you feel it in your bones, so magical it takes you places you have never been; so all-encompassing you’re not just peeking through the window, but part of the action.”[28] Thus, despite the commercialized differences in these places, I draw this comparison to show IMAX is not the only place cognizant of the importance of sensory stimulation in movie going. They each demonstrate how both commercialized and non-commercialized industries are recognizing the importance of exploring a 7th sense to bring back what initially attracted people to cinema.

John Grierson first defined documentary in the 1930s as being a “creative treatment of actuality,” acknowledging the creative outlet that documentaries also represent.[29] In the case of IMAX, their creative outlet lies not only in the narratives they tell but also in its game-changing technology. Cinerama was an example as to how technology continues to be a player in the growth of documentary filmmaking, as it also introduced a new form of projection that refreshed the movie-going experience into a spectacle. As time progressed, these widescreen formats became more sophisticated where IMAX was born, introducing new and even more immersive ways to illustrate documentaries. IMAX’s documentary narratives would cease to be the same without their 3D technology and vice versa; they portray the world in ways no other documentary formats can compare, as they’ve become leaders in trying to portray the real via advanced 3D technologies. IMAX has combined documentary’s factual and fictional elements in its deception also through its technology; in doing so IMAX has brought the magic back to cinema, leaving their audiences to feel inquisitive yet convinced of what they just saw. IMAX’s technology has not only enhanced the validity of documentaries through the reactions of its spectators, as a critic described their experience as being like “the first time you have an In-N-Out Burger, and then realize you can never step foot in a McDonald’s ever again;”[30] what’s more, it has expressed a desire to move from the confines of two-dimensional representations, to the wealth of a three-dimensional space, repairing the dormancy of cinema in the process.[31]

—-

References

- Belton, John. Widescreen Cinema. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1992.

- Belton, John. “Digital 3D Cinema: Digital Cinema’s Missing Novelty Phase.” Indiana University Press, 2012. 187-195.

- Elsaesser, Thomas. “The ‘Return’ of 3-D: On Some of the Logics and Genealogies of the Image in the Twenty-First Century.” Chicago Journals, 39.2: 2013. 217-46.

- Liszewski, Andrew. “IMAX’s New Laser Projectors Make Me Wish I Lived In a Movie Theater.” Http://gizmodo.com/imaxs-new-laser-projectors-make-me-wish-i-lived-in-a-mo-1689480610. Gizmodo, 5 Mar. 2015. Web.

- Nichols, Bill. Introduction to Documentary, 2nd Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010.

- Winston, Brian. “The Documentary Film as Scientific Inscription.” Theorizing Documentary. New York & London: Routledge, 1993.

- “About IMAX.” IMAX. IMAX Corporation. 2015. Apr. 2015. https://www.imax.com/about/

- “Sensory Ethnography Lab.” Sensory Ethnography Lab. President & Fellows of Harvard College. 2010. Apr. 2015. https://sel.fas.harvard.edu/

[1] John Belton, “Widescreen Cinema”, Cambridge, Massachusettes: Harvard University Press, 1992, p. 93.

[2] Ibid., 93.

[3] Ibid., 95.

[4] Ibid., 85.

[5] Ibid., 95-96.

[6] Ibid., 96.

[7] John Belton, “Widescreen Cinema”, Cambridge, Massachusettes: Harvard University Press, 1992, p. 97.

[8] Thomas Elsaesser, “The ‘Return’ of 3-D: On Some of the Logics and Genealogies of the Image in the Twenty-First Century,” Chicago Journals 39.2, 2013. p. 236.

[9] John Belton. “Digital 3D Cinema: Digital Cinema’s Missing Novelty Phase,” Indiana University Press 24, p. 195.

[10] Bill Nichols, “Introduction to Documentary 2nd ed.”, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010, p. 121.

[11] Brian Winston, “The Documentary Film as Scientific Inscription”, New York & London: Routledge, 1993, p. 53.

[12] Thomas Elsaesser, “The ‘Return’ of 3-D: On Some of the Logics and Genealogies of the Image in the Twenty-First Century,” Chicago Journals 39.2, 2013. p. 225.

[13] Andrew Liszewski, “IMAX’s New Laser Projectors Make Me Wish I Lived In a Movie Theater.” Http://gizmodo.com/imaxs-new-laser-projectors-make-me-wish-i-lived-in-a-mo-1689480610, Gizmodo,

[14] Bill Nichols, “Introduction to Documentary 2nd ed.”, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010, p. 69.

[15] Ibid., p. 69.

[16] Ibid., p. 17.

[17]Thomas Elsaesser, “The ‘Return’ of 3-D: On Some of the Logics and Genealogies of the Image in the Twenty-First Century,” Chicago Journals 39.2, 2013. p. 221.

[18] John Belton. “Digital 3D Cinema: Digital Cinema’s Missing Novelty Phase,” Indiana University Press 24, 2012 p. 191.

[19] Thomas Elsaesser, “The ‘Return’ of 3-D: On Some of the Logics and Genealogies of the Image in the Twenty-First Century,” Chicago Journals 39.2, 2013. p. 235.

[20] These films are not IMAX specific, but help paint a larger narrative as to how 3D can influence filmmakers in general, as well as its effects on the audience/critics through Nick James’ critique.

[21] Thomas Elsaesser, “The ‘Return’ of 3-D: On Some of the Logics and Genealogies of the Image in the Twenty-First Century,” Chicago Journals 39.2, 2013. p. 237.

[22] Thomas Elsaesser, “The ‘Return’ of 3-D: On Some of the Logics and Genealogies of the Image in the Twenty-First Century,” Chicago Journals 39.2, 2013. p. 240.

[23] Ibid., p. 240.

[24] John Belton. “Digital 3D Cinema: Digital Cinema’s Missing Novelty Phase,” Indiana University Press 24, 2012, p. 188.

[25] Ibid., p. 190.

[26] Thomas Elsaesser, “The ‘Return’ of 3-D: On Some of the Logics and Genealogies of the Image in the Twenty-First Century,” Chicago Journals, 39.2, 2013. p. 227.

[27] “Sensory Ethnography Lab”, Sensory Ethnography Lab, President & Fellows of Harvard College, 2010, Apr. 2015. https://sel.fas.harvard.edu/

[28] “About IMAX”, IMAX, IMAX Corporation, 2015, Apr. 2015. https://www.imax.com/about/

[29] Bill Nichols, “Introduction to Documentary 2nd ed.”, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010, p. 6.

[30] Andrew Liszewski, “IMAX’s New Laser Projectors Make Me Wish I Lived In a Movie Theater.” Http://gizmodo.com/imaxs-new-laser-projectors-make-me-wish-i-lived-in-a-mo-1689480610, Gizmodo,

[31] Thomas Elsaesser, “The ‘Return’ of 3-D: On Some of the Logics and Genealogies of the Image in the Twenty-First Century,” Chicago Journals, 39.2, 2013. p. 229.

Academia

What is USC’ Media Institute for Social Change?

The Media Institute for Social Change, known as MISC, is a production and research institute at the USC School of Cinematic Arts focused on using media as a tool for effecting social change. Founded in 2013 by Michael Taylor, a producer and Professor in the School’s famed Film & Television Production Division, the MISC maxim is that “entertainment can change the world.” It spreads this message by producing illustrative content, and by mentoring student projects, awarding scholarships and leading research. “We are training the next generation of filmmakers to weave social issues into their films, television shows and video games,” says Taylor. “As creators the work we do has a huge impact on our culture and that gives us an opportunity to influence good outcomes.”

In recent years MISC has partnered with organizations including Save the Children, National Institutes of Health and Operation Gratitude, and creative companies like Giorgio Armani, the Motion Picture Association of America and FilmAid, to create groundbreaking work that have important social issues woven into the narrative. MISC also worked with USC’s Keck School of Medicine to create Big Data: Biomedicine a film that shows how crucial big data has become to creating breakthroughs in the medical world. Other MISC films include the upcoming The Interpreter, a short film centered on an Afghan interpreter who is hunted by the Taliban, and The Pamoja Project, the story of 3 Tanzanian women who determined to help their communities by immersing themselves in the worlds of microfinance, health and education. MISC has also partnered with the app KWIPPIT to create emojis that spread social messages. Together they co-hosted the Project Hope L.A. Benefit Concert to spread awareness about the massive uptick of homelessness in Los Angeles.

The Power of the PSA or How to Change the World in 30 Seconds, which documented the institute’s collaboration with the Los Angeles CBS affiliate KCAL9 to make PSAs on gun violence, internet safety, and PTSD among veterans. Another MISC-sponsored film, Lalo’s House, was shot in Haiti with the intention of exposing the child trafficking that is rampant there and in other countries, including the United States. The short film (which is being made into a feature) was used by UNICEF to encourage stricter legislation prohibiting the exploitation of minors, and has won several awards, including a Student Academy Award.

“Our goal,” says Taylor, “is to send our students into the industry with the skills and desire to make entertainment that has positive impact on our culture.” The dream is a variety of mass-media entertainment where social messages aren’t an afterthought but are central to the storytelling.

For more about MISC and its projects, go to uscmisc.org.

Media Impact

Can We Believe The Gillette Ad?

The new Gillette Ad. It’s Pepsi #2. It’s poorly executed, laden with half-hearted strategy, an elephant in the China shop of gender relations.

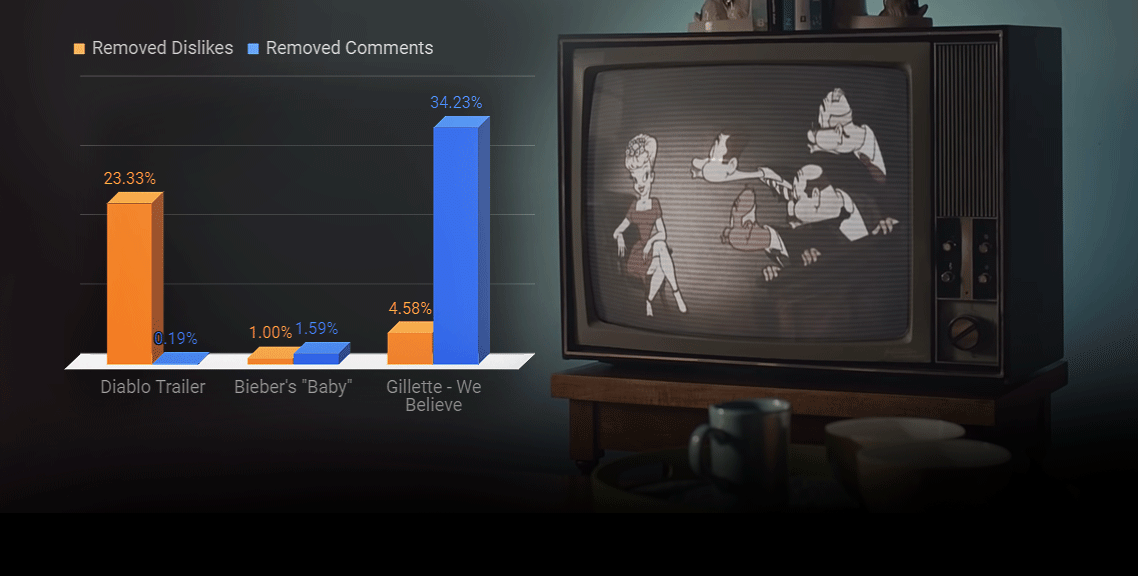

Numerically speaking, it’s not what it seems to be either. 34% of the ad’s comments were deleted, far more than other videos in similar dislike territories. Gillette’s account might just have set the YouTube proportional record for deleting comments on a single video (the absolute record goes to YT’s own Rewind 2018).

Taking Count – What Numbers Are Real on YouTube?

There have been repeated claims, mostly by YouTube commentators, that dislikes and comments were deleted. Another claim group was that the proportion of likes to dislikes seemed manipulated since it changed from a 10:1 ratio to a 2:1 ratio within days. Some outlets picked up the story, but nobody dove much deeper than a few screenshots. Well, after a few days and 3.000+ measurements we have answers for you.

With the help of YouTube’s API and Archive.fo’s screenshots of the video’s public numbers, we were able to test the claims of whether Gillette’s dislike and comment count were being subject to unusual moderator deletion.

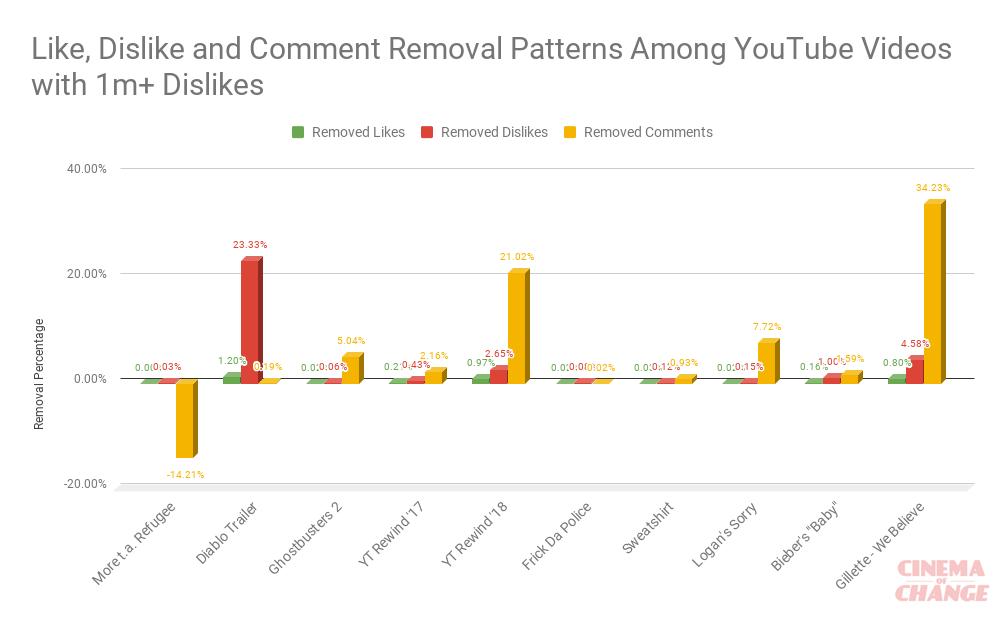

Before we ask that though, it’s important to know how much moderation usually goes on in other controversial videos. If it’s common to delete a certain amount of comments/dislikes, then the criticism of Gillette isn’t directly fair – it’d just be part of the YouTube ecosystem. To get a litmus test of “how common is comment/dislike moderation in similarly controversial videos”, we used a few close neighbors in the List of most disliked YouTube videos as comparables and measured the front-end/back-end discrepancy.

One of them was a “Diablo” game trailer that also received criticism that the publisher had deleted comments and dislikes. Our research was simple – we made API queries to YouTube’s server back-end over the course of a few days while manually transcribing screenshots of the front-end from Archive.fo for similar time spans. While YouTube’s server keeps all video interactions on record, even fraudulent or bot-based ones, the public front-end is influenced by a filtering mechanism that hides certain interactions.

Claim 1: The Gillette Ad Had A Manipulated Growth Pattern

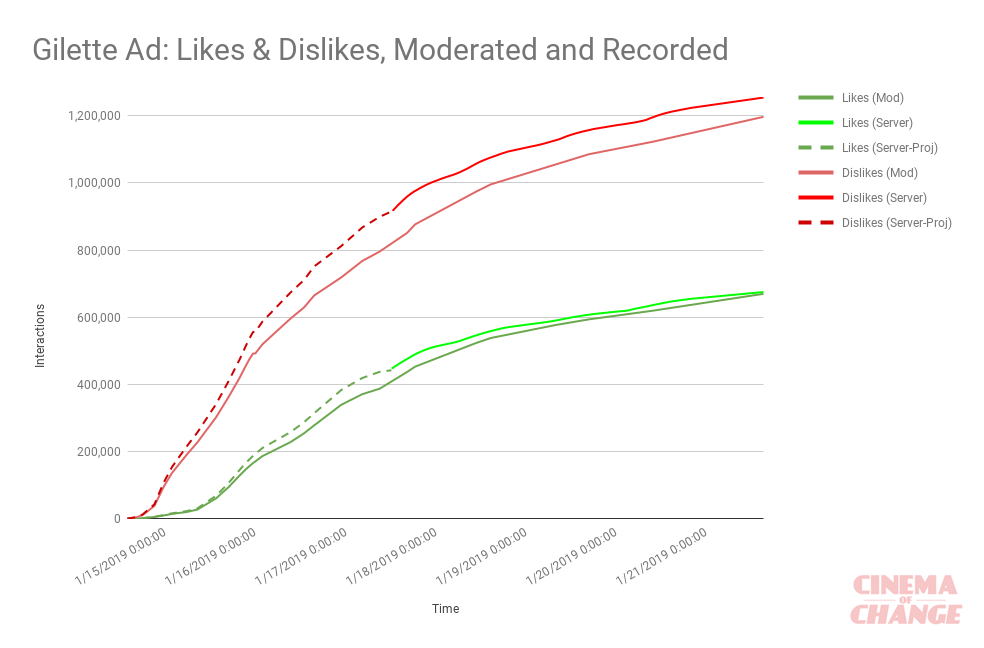

There was nothing really unusual about the growth pattern of likes and dislikes in the Gillette video while we were measuring it. But we started measuring server data on Day 3 of the video being public – the first 3 days we only know from public screenshots, and can project how the deletion pattern must have created a difference.

The growth and change of server-side as well as public facing likes and dislikes on the Gillette “We Believe” ad on YouTube.

You can see that in the beginning, dislikes took off very quickly, while likes had a slower growth, but eventually the growth rates approximately equalized, so now there’s a constant 500k lead on dislikes to likes. This is a simple explanation for the changing ratio from 10:1 to 2:1, and we have reason to believe there was no foul play at work there.

Interestingly enough, while there are more dislikes than likes that were hidden by moderators, the likes count disparity shrinks as time goes on, essentially un-hiding likes again. This might be a technical glitch, since a similar shrinkage of hidden dislikes seems to be going on as well.

The archival data only records public likes and dislikes, not comments – so we aren’t sure about the comment deletion pattern over time.

Like data? Take a look at the public spreadsheet.

Claim 2: A High Number of Dislikes and Comments Were Deleted

What was far more surprising to see was the comparison to other highly disliked videos. The server queries resulted in two real outliers – Diablo’s massive deletion of dislikes, and Gillette’s outstanding number of comment deletions. While Blizzard eradicated 220k dislikes on its Diablo Immortal trailer (that’s 23% of the total) from public view (Gillette only deleted 5%, slightly above average), Gillette deleted a whopping 34% of its comments – 172,000 comments to be precise. This is closely followed by YouTube’s own 2018 Rewind video, which has 21% of its comments removed and is the most-disliked video in YouTube history.

Gillette deleted a potentially historic fraction, 34%, of its comments on the “We Believe” video. Blizzard removed 220,000 dislikes on its worst received game trailer, and YouTube banned 21% of the comments on the latest Rewind video.

Here’s the underlying spreadsheet for that data.

There’s a reasonable argument that the comments on Gillette’s ad were so hateful that they had to be deleted, and the primary fuel to that fire would be the implicit attack on men in general, or the explicitly feminist message. The argument is solid when examining anti-feminist culture on YouTube; Feminist Frequency has their comments and likes disabled since the Gamergate controversy (also on server side), the most-watched pro-Feminist video is a TED Talk and has about 3,000/15% of comments deleted. Then again, semi-viral videos that would fit the “men will feel uncomfortable” category, like the Billie Bodyhair campaign or 10 hours of walking in NYC as a woman or #ustoo PSA, don’t have strong deletion patterns (approx. 1-2%).

If we want to know why Gillette proportionally deleted more comments than anyone else in that league, there’s only one way to know: For Gillette to give the public some insights in what their deletion policies looked like.

Note 1: “More than a Refugee” somehow has more comments publicly displayed than the server-side API query counted – I’m not sure how that’s even technologically possible.

Note 2: After talking with a number of large-channel YouTube managers, I was told that it was not possible to delete dislikes. Well – Blizzard’s 20% dislike deletion shows that YouTube makes exceptions.

Not Just Numbers – Let’s Talk Impact

After analyzing the numbers on YouTube engagements, the question to ask is: How did this happen? Why was the blowback so severe? Gillette was in a unique position to turn the gender relations conversation into a very engaging campaign that would have mobilized people positively. But they didn’t. Instead of focusing on progress, they focused on ambiguous, polarizing messaging.

In short, the “We Believe” ad was a waste of Gillette’s potential. And here is why.

I am all for purpose-driven marketing. I spend day and night thinking about and actually producing impact-driven content. And when that kind of advertising is done right by big agencies, it’s really quite incredible to watch positive impact unfold.

Well-Executed Campaigns as Primers

Take the Kaepernick ad by Nike. It asks people to dare to “dream crazy”, and took a political stance against the oppression of black people in the U.S by featuring Colin. That gamble played out well; the backlash was outweighed by support, and the market responded positively for a good run.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fq2CvmgoO7I

.

Or remember the Winter Olympics ad, “Proud Sponsor of Moms”? Guess who did that. P&G, parent company of Gillette. Everyone loved that. And in case you don’t watch much advertising, they did more of those, with bold themes and increasingly diverse casting.

P&G followed it up by tastefully celebrating black people’s identity and appearance with “Dear Black Man”:

.

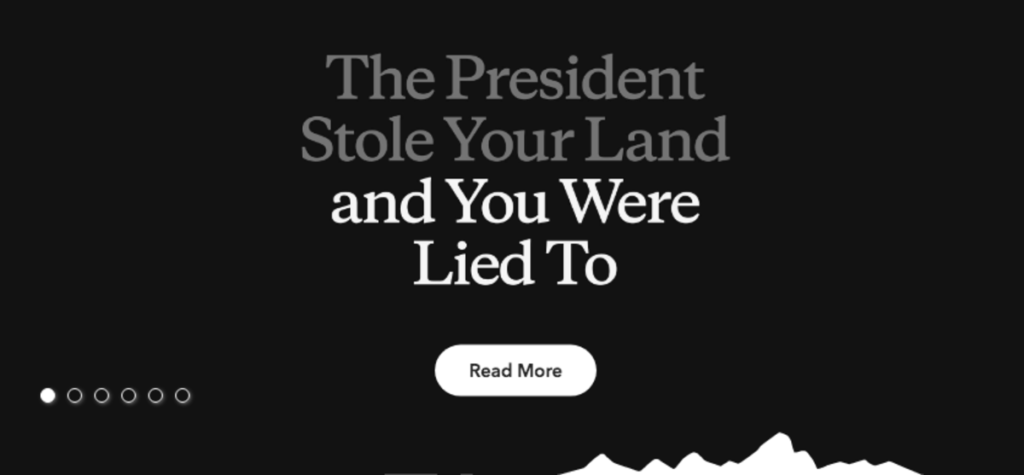

Patagonia didn’t even use a video – they just turned their website dark and said “The President Stole Your Land” as a response to Trump’s threatened shrinkage of National Parks, and then sued him. The market liked it.

There are countless other examples of brands choosing more aware, purpose-driven marketing campaigns.

Watch at least a few of those above to get a primer of “what works”.

What all of them have in common is that they picked an impact area that was either agreeable to most their viewers, or close enough to their company ethos that controversy wouldn’t erode their loyal, primary customer base.

How Not to Do It: Gillette Ad & Pepsi Ad

Now compare this with the below:

Pepsi – “Jump In”:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dA5Yq1DLSmQ

Gillette – “We Believe: The Best Men Can Be”:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=koPmuEyP3a0

.

Pepsi co-opted a social movement with a reality TV character and then preached unity when the world looked starkly divided. And even though some Pepsi drinkers might also watch the Kardashians, they saw through the half-hearted charade: Pepsi had nothing to do with activism, period. It was an “out of the blue” decision to capitalize on something happening in the world, and it felt fabricated.

Gillette did the same. Gillette has nothing to do with feminism, or with anti-bullying. Someone at Gillette decided to make this a cause out of the blue.

Gillette co-opted legitimate movements and issues like #metoo, but instead of sheepishly celebrating a soda version of a harsher reality like Pepsi did, it opened with s bad apples as representatives of its core base without delineation, and then sprinkled in a sugar coat of suggestions for all men on how to be better. Nothing new there, it’s just political now.

As a reality check, “toxic masculinity” is a pretty confusing nomer for negative aspects of masculinity. A Gillette ad for women opening with “Abusive women” wouldn’t work just like a US Army ad opening with “Un-patriotic Americans”. The conflation of two words creates ambiguity outside of an academic debate – is the adjective-noun pair describing the quality of the noun, or is it referring to a sub-part of the noun that matches the adjective? To further go into a grey zone, the “toxic” voice over is largely drowned out by “harassment” in the ad, resulting in a “sexual harrassment masculinity” sound upon first listen.

We’re not on a college campus dissecting word pairs here – we are in the world of impact-driven advertising to mass audiences, and you can’t afford ambiguity in this arena. Anyone that looks past these sloppy linguistic choices is providing Gillette a biased playing field.

.

The rest of the video is full of caricatures of bad men mixed with normal men, and an eventual return to “being the best”.

But by then, the base has tuned out, and Gillette has lost. Not only many of their customers, but an opportunity: To actually reshape and contribute to masculinity. To actually make an ad that men will watch, will love, will share, and will actually make them better men. An ad that all men can agree with, without reservations. An ad that doesn’t open with bad apples as representatives. An ad that encourages men to be present in their boys’ lives. A campaign against bullying.

Something that every man can stand behind, and a standard that we’re all proud to live up to. But that chance was wasted for something phony.

Gillette’s skin-tight ads in 2011 remind us of what the brand used to think about women – and how it appealed to similar sentiments it now criticizes, without acknowledging the hypocrisy.

Looking Inward and Forward to Do Better

Why do so few see the charade here?

Gillette could have acknowledged its treatment of women for the past 100 years and apologized, if they wanted to. Nobody really seems to see the irony in applauding to the feminism of the ad and Gillette’s unacknowledged past in contrast.

How about something as complicated as implicit biases by men (like what the boardroom scene tried to address)? Well, they could have done a boy’s version of their Always Ad #LikeAGirl (it’s a bit clunky but the idea is highly effective, and I’m sure it’d have worked with boys too).

All these topics take time and care to implement in separate campaigns. Gillette’s current ad is the impact equivalent of a “YouTube Rewind”, and is heading into similar mashup-dislike-count territory. There have been prior (Harry’s) and later (Egard) attempts to make “men’s issues” themed feel-good ads, but nothing comes close to the “primer” ads on the top, which had an impact edge to them.

A new Adweek Article suggests that the ad was primarily meant for women in the first place, to change their perception of shaving from “disgust” to “joy”. It’s a bit questionable to criticize men as a vehicle to position the brand better for women.

Doing ads that honestly criticize without alienating – that is hard. To Gillette’s credit, they at least failed at something challenging – and that is brave.

Non-Profit Tie-Ins Need Care, Not Just Cash

To finish on a slightly hopeful note – it’s wonderful that Gillette decided to donate $1M to the Boys & Girls Clubs of America. Awesome. But that’s all that Gillette had to say on their new thebestmencanbe.org website. No roll-out, no strategy, no content, no pipeline – just a promise of money and a single link to a great nonprofit. That’s the laziest impact follow-through effort I’ve seen in a long time. Sloppy ad, good nonprofit choice, obvious lack of involvement in the actual impact.

Gillette is a big company, and they can absorb a blow. 1.1M dislikes on YouTube isn’t even close to what Justin Bieber gets. But unlike Gillette, Bieber’s team left the negative comments rather untouched.

.

In the world of purpose-driven advertising, I like to hold companies, agencies and decision-makers to higher standards. Not a peer-pressured applause for intentions, but well-earned respect for nuanced execution and actual impact.

Because we all can be better.

And Gillette should be the best they can be.

Companies

Aging and Nuclear War in the Writers’ Room

Have you ever heard of Hollywood, Health, & Society? Most likely not.

Yet, you have probably watched something that they have worked on. With over 1,100 aired storylines from 2012-2017 including those for Grey’s Anatomy, NCIS, and black-ish, Hollywood, Health, & Society (HH&S) serves to provide entertainment industry writers with accurate information on storylines related to health, safety, and national security. This pretty much includes everything from aging to nuclear war.

For example, that April 30th, 2017, episode of American Crime that included immigration, opiate abuse, and human trafficking in the plot? Data analysis is currently in progress for a cross-sectional study of viewers.

With the USC Annenberg Norman Lear Center, HH&S not only pairs experts with writers, but also conducts extensive research on their impact and the correlation between seeing things on screen and audiences’ changed perceptions of those topics. HH&S maintains a low public profile, but is very much involved in the writers’ rooms and guilds. Their approach is two-fold:

1) Reactive – responding to requests and needs for HH&S services, which manifests in the form of phone calls and/or emails to the center, expert consultations, guidance on accurate language.

2) Proactive – introducing writers and entertainment professionals to subject matter experts through panel discussions, screenings and immersive events; a quarterly newsletter, tip sheets and impact studies.

Students, you are welcome to use this resource as well! HH&S serves writers at all stages of their careers, although of course, shows on the air or already in production have priority.

To learn more about the research and impact studies behind HH&S:

– Featured list of tip sheets for writers

– CDC’s list of tip sheets from A-Z

– On location trips for writers to gain understanding for certain topics

Follow Hollywood, Health, and Society on Facebook and Twitter to stay updated with their work and upcoming opportunities.

-

SIE Magazine9 years ago

SIE Magazine9 years agoWhat Makes A Masterpiece and Blockbuster Work?

-

Filmmakers9 years ago

Filmmakers9 years agoFilms That Changed The World: Philadelphia (1993)

-

Companies6 years ago

Companies6 years agoSocial Impact Filmmaking: The How-To

-

Media Impact5 years ago

Media Impact5 years agoCan We Believe The Gillette Ad?

-

SIE Magazine9 years ago

SIE Magazine9 years agoDie Welle and Lesson Plan: A Story Told Two Ways

-

Academia8 years ago

Academia8 years agoFilmmaking Pitfalls in Deal-Making and Distribution

-

Academia8 years ago

Academia8 years agoJoshua Oppenheimer: Why Filmmakers Shouldn’t Chase Impact

-

Filmmakers9 years ago

Filmmakers9 years agoStephen Hawking vs The Elephant Man