Companies

Social Impact Filmmaking: The How-To

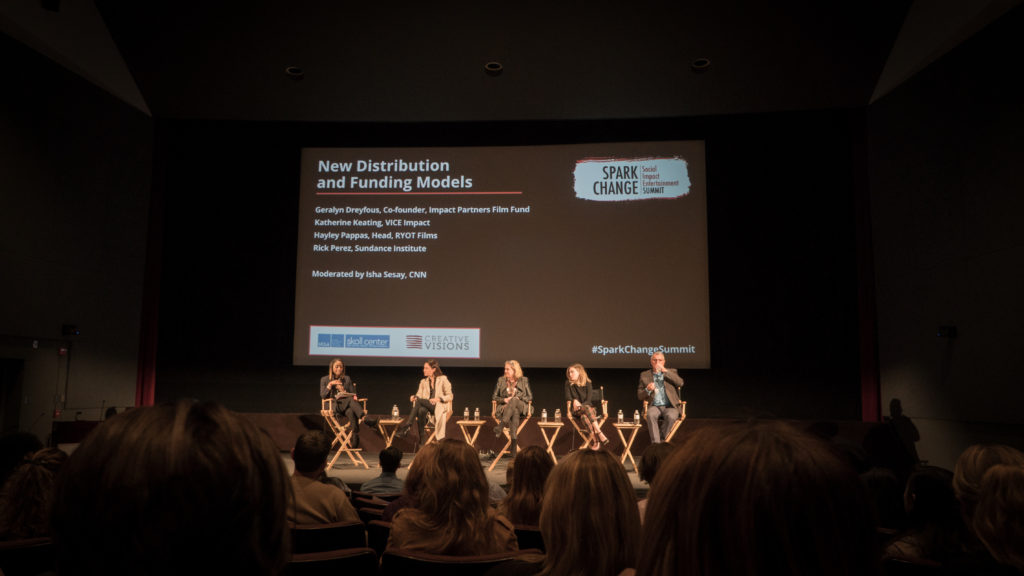

“Social impact entertainment’s time has come,” Teri Schwartz, the dean of UCLA School of Theater, Film, and Television said as she welcomed everyone to the first Skoll Center summit. Nonprofit leaders, social campaign strategists, experts in distribution and funding, and a variety of creators gathered to define social impact entertainment, learn more about storytelling, and discuss new distribution and funding models.

Students and professionals alike joined in the conversation thinking about questions like: Is intention enough? What is the difference between storytelling and advocacy? What are examples of previously successful social impact campaigns and how can we follow those models? In this time of mass streaming platforms, how can artists market their social impact content and demand awareness?

The social impact entertainment field is developing, but very much alive. However, unlike industries that sometimes hide information to maximize self-growth, it is critically important for us to collaborate in this space and build a community of entertainment activists. Cinema of Change sent several to this summit to do exactly that: share what we’ve learned and be honest about what we don’t know yet.

So, what’s the secret sauce? How can films change the world?

Truth is, like the entertainment industry itself, there is not one path to ending climate change or human trafficking through film (unfortunately, I know). However, whether it is documentary, narrative, or docu-fiction, everything begins with storytelling.

-

STORYTELLING

No matter how important the statistics are or how beautiful the production design is, people are not going to watch a film that has no story. Sometimes, that is why a narrative film may even have a larger impact on a social issue than a documentary film because people relate and empathize to the fictional characters more and will walk away with those emotions in mind.

Holly Gordon, Chief Impact Officer of Participant Media: There’s a difference between storytelling and advocacy. Storytelling comes 100% from intention, but also creativity. “Creativity means intention and the ability to tell a story.” And that’s what leads to transformational change, which is long-term and visionary, compared to transactional change.

Hayley Pappas, Head of RYOT: As a reminder, “It doesn’t always have to be heartbreaking to be transformative. You can laugh a lot and see something in a new way.”

Davis Guggenheim, director of An Inconvenient Truth and He Named Me Malala: “Without the intention, you’re not going to do it. It’s too hard.” Documentaries can hit a wall sometimes because everyone working is so passionate about the topic, but when you go into the editing room, there’s no story.

As much as we support documentaries here at Cinema of Change, we also believe that mega blockbusters and social impact are not mutually exclusive. In fact, we wrote an article on exactly why we think the opposite here.

Darnell Strom, Creative Artists Agency: “Story matters. Representation on screen matters and that has a ripple effect.” Sometimes, filmmakers may not set out to have a specific intention, yet organic social issue campaigns arise from a great story. Take Black Panther for example. Disney probably did not set out to create a transformative piece about black culture through a Marvel comic book story, but the film had a majority black cast and depicted a woman leading the technological developments. Now, nonprofits are jumping up about women in STEM and young black boys and girls can watch the film and be like, Hey, if someone who looks like me can do it, so can I.

-

MEASURING SOCIAL IMPACT

Great, this film tells an incredible story about a disadvantaged youth rising from poverty and attending a prestigious university, but how do we measure the social impact? In other terms, how do we calculate the number of minds changed, or decisions made to take action? Even Gordon agreed that transformational change is very hard to measure, but it can be done.

Holly Gordon: For Girls Rising, which is both a film and nonprofit about the importance of educating young girls, measurement meant hiring Mission Management to analyze impact in three ways: changed minds (reach), changed lives (money raised), and changed policy (shifts in government policy). Gordon worked on relationship building with a number of nonprofits and even leaders like Michelle Obama to develop impact partnerships and shape campaigns around the themes in the documentary, before a single frame was even shot.

Rory Kennedy, director of Last Days in Vietnam and Ghosts of Abu Ghraib: Social impact is often thought of in large numbers: raising millions of dollars, changing thousands of lives, but it is also just as important on an individual level. For example, in Last Days in Vietnam, Stuart Herrington, a counterintelligence officer in the Vietnam War, was responsible for safely evacuating American soldiers at end of the war, but he knowingly left 422 Vietnamese soldiers there despite promising them safety. At the premiere of the documentary, Harrington reflected on his guilt and regret for leaving all those lives behind and said that he dreaded ever meeting one of the 422. Sure enough, one of the Vietnamese soldiers Harrington left walked up on stage and told him, “I forgive you.” That moment left both of the men in tears and it may not have changed a hundred lives, but it changed two.

-

IMPORTANCE OF SOCIAL IMPACT CAMPAIGNS

When a film wraps, the awareness and campaign work most definitely does not. Social impact campaigns are critical to accelerating awareness and creating a sustainable, lasting effect. They’re arguably more effective when launched before the film even begins production.

Bonnie Abaunza, founder of The Abaunza Group which has launched campaigns for The Hunting Ground, Hotel Rwanda, Cries from Syria: These impact campaigns are designed to intersect all industries and companies. Impact comes from educating students, mobilizing ambassadors, challenging companies, and partnering with nonprofits and policy leaders who care. One example of a highly successful social impact campaign is the one for Blood Diamond. Lena Khan, the director of The Tiger Hunter, even told Abaunza that she has a conflict-free diamond on her hand because of the film. Jewelry companies like Tiffany & Co. joined the movement by labelling their diamonds as “conflict-free” especially because more and more people started asking about it. Amnesty International created an entire curriculum to introduce the issue to students.

Ted Richane, Vulcan Productions Impact and Engagement: At the end of the day, “We can have our strategies, but the best thing we can do is listen. The community is awesome and going to be inspired and go to take the issue upon themselves.” That’s the ultimate goal, right? Launch the campaign, tell the story, and empower others to share and do something about it all.

-

DISTRIBUTING AND FUNDING SOCIAL IMPACT FILMS

The world of distribution and funding can be quite daunting to enter, because no matter how passionate someone is, it is always difficult to get the money needed to transform passion into action. Major companies are also a huge part of the conversation. How do they decide what films to green light? How can indie artists break out with both an entertaining film and one that creates change?

Geralyn Dreyfous, Co-founder of Impact Partners Film Fund: There is a shift nowadays in the distribution world. Only two films sold at Sundance this year. Netflix is commissioning their own content. Companies are not paying their creators enough, especially for short form content. To the artists: “You love it so much, you’d do it for free. But you have to stop doing it for free.” When starting out with trying to find investors, you can always pitch to the Impact Partners Film Fund, but if you’re not successful there, think about incentives and break up your budget into smaller chunks for financing. Can you give donors credits, on screen thanks, private screenings, and other benefits? “Mostly, founders are interested in amplifying and aligning your content with their philanthropic goals. They need to know that you’re the person to tell that story.”

Katherine Keating, Vice Impact: With a cross-platform company like Vice, it’s very important to think about who the audience is and where they are consuming their content. Some things are meant to be a series of five 1-minute shorts on Facebook, even though the artist may have pitched it as five 1-hour series. Another way to integrate the impact campaign is through brand partnership with large, respected companies. For example, Colgate, one of the biggest toothpaste sellers, is now promoting water conservation and looking at ways to reduce plastic use in their packaging. Companies are starting to recognize the importance of social impact and it’s our job as their commercial creators to push them in that direction.

Cinema of Change previously interviewed entertainment attorney Mark Litwak about the “Filmmaking Pitfalls in Deal-Making and Distribution”; read what Litwak has to say here.

NOW WHAT?

“To create in this chaotic world peace, to seek in this gathering darkness light, to transform the hatred into a new kind of loving. Together, we can transform this world. It’s going to be really hard. But we can do it, and it will be through storytelling and courageous people like you.” (Kathy Eldon, Co-founder of Creative Visions). With that, the SPARK CHANGE Social Impact Entertainment Summit came to end, but our work is just beginning.

As audiences, we have to demand for content that does not further marginalize communities and perpetuate stereotypes.

As companies, we cannot stay silent to the injustices in our world in order to protect our brand.

As filmmakers, we are not just producing beautiful, cinematic pieces. We have the responsibility to use those creations to spark change.

—

List of all organizations in attendance: Cause Cinema, CNN, Creative Activists Network, Creative Artists Agency, Creative Visions (co-host), Google, I am Jane Doe, Impact Partners Film Fund, Living on One, Majority Film, Participant Media (sponsor), President’s Committee on Arts and Humanities, RYOT, Skoll Center (co-host), Sundance Institute, The Abaunza Group, Vice, Vulcan Productions (sponsor) UCLA School of Theater Film Television

*Sayings in quotation marks are directly quoted. Other remarks are paraphrased.

Companies

Aging and Nuclear War in the Writers’ Room

Have you ever heard of Hollywood, Health, & Society? Most likely not.

Yet, you have probably watched something that they have worked on. With over 1,100 aired storylines from 2012-2017 including those for Grey’s Anatomy, NCIS, and black-ish, Hollywood, Health, & Society (HH&S) serves to provide entertainment industry writers with accurate information on storylines related to health, safety, and national security. This pretty much includes everything from aging to nuclear war.

For example, that April 30th, 2017, episode of American Crime that included immigration, opiate abuse, and human trafficking in the plot? Data analysis is currently in progress for a cross-sectional study of viewers.

With the USC Annenberg Norman Lear Center, HH&S not only pairs experts with writers, but also conducts extensive research on their impact and the correlation between seeing things on screen and audiences’ changed perceptions of those topics. HH&S maintains a low public profile, but is very much involved in the writers’ rooms and guilds. Their approach is two-fold:

1) Reactive – responding to requests and needs for HH&S services, which manifests in the form of phone calls and/or emails to the center, expert consultations, guidance on accurate language.

2) Proactive – introducing writers and entertainment professionals to subject matter experts through panel discussions, screenings and immersive events; a quarterly newsletter, tip sheets and impact studies.

Students, you are welcome to use this resource as well! HH&S serves writers at all stages of their careers, although of course, shows on the air or already in production have priority.

To learn more about the research and impact studies behind HH&S:

– Featured list of tip sheets for writers

– CDC’s list of tip sheets from A-Z

– On location trips for writers to gain understanding for certain topics

Follow Hollywood, Health, and Society on Facebook and Twitter to stay updated with their work and upcoming opportunities.

Academia

Filmmaking Pitfalls in Deal-Making and Distribution

Welcome to the Cinema of Change podcast with Tobias Deml and Robert Rippberger. Cinema of Change is a magazine and community that challenges the conventions of film and its ability to effect change in the world. This episode is an interview with entertainment attorney Mark Litwak called, “Filmmaking Pitfalls in Deal-Making and Distribution.”

Mark Litwak is a veteran entertainment attorney. As a Producer’s Representative, he assists filmmakers in arranging financing, marketing and distribution of their films. Litwak has packaged movie projects and served as executive producer on such feature films as “The Proposal,” “Out Of Line,” “Pressure,” and “Diamond Dog.” He has provided legal services or worked as a producer rep on more than 200 feature films.

Litwak’s significance can be see in Disney’s Wreck it Ralph – where the filmmakers decided to name the owner of the arcade which encapsulates the entire plot, “Mr. Litwak”.

Content of this Episode:

- 0:22 – Introduction

- 1:33 – After learning filmmaking, what business pitfalls are common for young filmmakers?

- 5:15 – How is the Film Industry like the Wild West – creatively and in dealmaking?

- 9:11 – How can first-time filmmakers survive the Sharks in Sales and Distribution?

- 12:10 – Reporting the Bad Players: What was your Litwak Filmmakers’ Clearinghouse?

- 15:53 – CAM (Collection Account Management) – how do they help with accountability and fairness for the filmmaker?

- 19:52 – What happened to the Filmmaker’s Clearinghouse?

- 20:40 – Even Ethical Distributors will be out for their own best interest – is that true?

- 22:20 – What criteria do you base your client selection on? What homework should a filmmaker bring to a lawyer?

- 26:44 – How is New Media influencing the market and distribution?

- 34:38 – Can Indie Distribution even compete anymore with vertically integrated SVOD platforms like Hulu and Netflix?

- 39:03 – What progress can be made in the Filmmaker > Sales Agent > Distributor workflow?

- 42:44 – How can a producer put their best foot forward towards a lawyer?

- 45:50 – How can a filmmaker prepare for working with an Entertainment Lawyer?

- 46:46 – What resources exist in the film industry that even the playing field of sales and distribution a bit in favor of the independent filmmaker?

Litwak is also the author of six books: Reel Power, The Struggle for Influence and Success in the New Hollywood (William Morrow, 1986), Courtroom Crusaders (William Morrow, 1989), Dealmaking in the Film & Television Industry (Silman-James Press, 1994) (winner of the 1996 Kraszna-Krausz award for best book in the world on the film business), Contracts for the Film & Television Industry (Silman-James Press, 3rd Ed. 2012), Litwak’s Multimedia Producer’s Handbook (Silman-James Press, 1998), and Risky Business: Financing and Distributing Independent Film (Silman-James Press, 2004).

He is an adjunct professor at the U.S.C. Gould School of Law where he teaches entertainment law.

Litwak has a B.A. and M.A. degrees from Queens College of the City University of New York. He received his J.D. degree from the University of San Diego in 1977.

We hope you find this conversation interesting and insightful. Subscribe to make sure you don’t miss an episode. Until next time, be the change that you want to see in the world. Then turn it into cinema.

Companies

VRIDE: 360 Degrees inside of the Empathy Machine

The heart of the Sundance Film Festival is Main Street in Park City, Utah. It starts out as a packed street full of festival-goers and eventually tapers off into a relatively busy arrangement of pedestrians and shop windows.

It is on Main St. where boutiques and art galleries are temporarily converted into physical existences of Kickstarter, AirBnB, CNN Films, Canon Lounge and so forth. Next to the internet commerce taking space are various attractions specifically made for Sundance. The busiest this year is the “Next Frontier: Claim Jumper”, a 3-story building dedicated only to Virtual Reality. Here is where people stand in line for 1 hour or sign onto digital wait lines that can last 4 hours – so high is the popularity of the 35 attractions powered by the Samsung Gear VR (the “Oculus Light”), HTC Vive and other VR systems.

Across the street from this virtual amusement park is a quiet storefront that reads “C1 VR”. It took me 5 days to notice it, and I finally checked it out together with some Berkeley journalist friends. C1 is the abbreviation for Condition One, a startup based in Park City itself, which “creates “How big of an experience do you want?”, asks the lady in front. “I want the most intense thing you have”, spills the stimulus-addicted millennial in me.

“Then we’ll have you try our Factory Farm experience from Animal Equality.”

Nothing could have prepared me for what was to come.

Not Just Watching, But Being Present

An audience being fully immersed in their VR experience. The theater-like setting is not optimal, as the viewer is unable to take advantage of all 360 degrees of viewing. At Condition One, swivel chairs and plenty of leg space allowed for full spatial immersion in the VRIDE.

One of the main concerns in the quickly growing field of Virtual Reality is the concept of Presence. It is the requirement of VR immersion, namely the belief that one is actually present in the space that one is experiencing. any glitch, wrong refesh rate etc. takes you out of the suspension of disbelief and hence interrupts (tele-)presence.

How can we feel present in a space that literally only exists on a smartphone strapped to our head, with some lenses in front of our eyes and headphones on our ears? It’s not a fully resolved question, but we essentially fool our visual system into believing that what we see is completely real. Each eye usually gets a different image, creating stereoscopic imagery and a make-belive 3D effect just like you’d have it in a movie theater wearing 3D glasses. At the same time, there is no fixed screen any more; instead, the screen travels with your head and you experience it through circular goggles, which you soon forget about.

One of the most nifty components of our visual perception processing is our Vestibular System, where our body can sense acceleration and orientation. Imagine an accelerometer and a gyroscope, similar to the components of your smartphone, just built into our head right where our ears sit. Accelerating liquids in a 3-dimensional loop system tell our brain where we are currently looking and how strong the acceleration is. If there is an offset between the inputs of the Vestibular system and the inputs from our eyes, we become dizzy and call it motion sickness. Car sickness, sea sickness, simulator sickness – they’re all from the same family. Some of us have thrown up because of motion sickness, others just feel miserable. The evolutionary use? It’s one of the ways the body detects poisoning: If one sense delivers false or delayed information, it might be that the body has ingested a toxic substance and needs to expel it. Now that we have developed systems such as boats, cars and airplanes, our evolutionary biology is in slight disagreement with our technological evolution.

This is no different in VR, and any delays in the visual information can cause simulator sickness. But when everything is in perfect harmony and synchronization, when we have around 95 frames per second, the world inside the stereoscopic VR headset becomes a reality – and we become present in it.

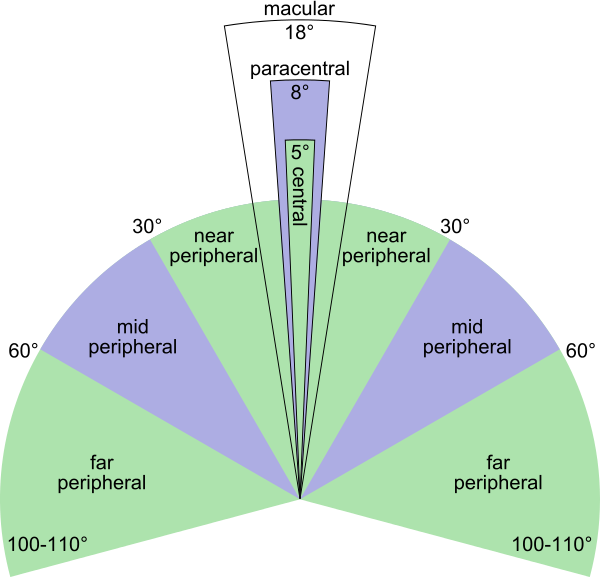

What makes VR unique now is that – usually – you have 360 degrees of movement freedom into any direction. When you look down, the image in front of your eyes seems so real yet your body is not present, that is a strange experience. It’s the experience of presence – the belief that the virtual reality around you has become real. With (usually dynamically generated as per orientation and motion) binaural audio fed through headphones (which provides us with stereophonic sound), the sense of reality becomes even stronger. This class of dynamically simulated sound delivered as stereo binaural audio is referred to as 3D Audio, and synchronizes perfectly with our head motions. It allows us to not only watch something, but actually exist within that space, as an invisible observer. What becomes apparent in this deduction is the great applicability of live action Virtual Reality experiences as an Immersively Documented Experience. I propose to abbreviate and classify these experiences as VRIDE (Virtual Reality Immersively Documented Experience).

Take Me on a VRIDE

Once we wear a simple VR set such as the Gear VR (the device Condition One uses to present its VRIDEs), the documentary filmmaker can take us anywhere in the world. It is a bit like watching the good old IMAX nature films that took us into the depths of the ocean, onto exotic islands or into outer space. While in the old IMAX experience, you had a vertical and horizontal (nearly square format) field of view of 90-150 Degrees. The sheer size of the IMAX screen allowed a viewer to feel fully immersed if they ignored their peripheral vision and didn’t move their head. These IMAX experiences were powerful – you’d see animals larger than life, and often feel close to nature despite sitting in a dark theater in an urban center.

Now, with VR, the full immersion into nature and environment can take place just about anywhere. Noise-cancelling headphones are obviously a requirement if the viewer is in a noisy environment, but other than that, the real world disappears once one goes on a VRIDE. In this experience, the passive viewer turns into an active observer – one is able to turn their head and observe the world in the most familiar of ways. In the case of Condition One, I was taken into an industrial pig farm and later a slaughterhouse. What becomes uniquely powerful in this scenario that differentiates a VRIDE from a, say IMAX experience or Facebook PSA video on animal cruelty, is the positional relationship between viewer and mediated subject.

Let’s imagine four scenarios: We see a pig being slaughtered in real life, we watch a pig being slaughtered on IMAX, we watch the killing in a Facebook video, or we experience the slaughter in a VRIDE.

- Real life observation: We will respectfully keep a distance to the pig, turn our head and cover our ears if it is too much, but have strong social pressure to not leave the room. All sensory organs transmit information to our brain that is consistent with “pig slaughter”, including taste and smell. When we look down or at our hands, the body is present. Most likely, we will be looking down at the pig, as it is much shorter than us.

-

IMAX experience: The screen is so big that even when we look away, we probably catch a glimpse of what is happening. The dark theater nearly disappears in our vision, so the viewer and the large screen are quite alone with each other. We can cover our ears if the sound is too much. Taste and smell are not affected at all. Most likely we will be looking down at the pig, as the IMAX cameras are large and need proper space on a tripod to be recording.

- Facebook video: The viewer sees their own hands, keyboard, a screen, a facebook interface, and finally, the video – all at once. Despite our central vision being mostly on the video, we still notice the whole world around us – wether that is a messy desk, a cafe or our hands holding the smartphone the video is playing on. Sound might or might not even be turned on. We can pause, scroll away or click away any second; it’s trained behavior. Most likely we will be looking down at the pig, as the video might have been recorded as a hidden camera on someone’s suit button, or as a Handycam video at shoulder level.

- VRIDE experience: Our body disappears completely, as does our environment that we are currently sitting or standing in. We can see 360 degrees around us, top and bottom. The camera rig is very small, so there’s a good chance that we are in the cage together with the pig, or right next to it on the floor as it is spasming and bleeding to death; the pool of blood forming around us. The sound is fully immersive, and our only option to end the experience or avoid the sound completely is to rip the entire gear off our head. The other option for avoidance we have is to turn away and stare at the ceiling or another part of the factory – but we’ll hear the squealing regardless. Smell, taste and touch stay unaffected.

It becomes very clear that the VRIDE is closest to real life, and while having a multitude of missing senses, the audiovisual experience in a VRIDE can be even more intensive than in real life. This is due to the ability of the filmmaker to choose perspective for us and i.e. place us inside the cage together with the pig – a place we would otherwise not have, were we just visiting the pig factory. Also, watching a pig from below rather than from above changes a lot about how we see the pig – inferior or superior to us, physically speaking. Watching it from below or its eye level places us in a position of equality and respect.

The VRIDE Empathy Machine

This change in perception is the reason why people call VR the new “Empathy Machine”. We as an audience are immersed in the life and environment of other humans, animals or plants. We’re body-less, seemingly invisible points of consciousness that can only observe and experience. It’s a strange feeling, but once the concept of Self disappears, so does one’s ignorance of the world around us. Since we ourselves no longer exist, that which is around us gets all of our emotional attention. VR turns us from a rather selfish main character in our own lives to an empathic observer in the lives of others.

A man experiencing Animal Equality’s VRIDE “Factory Farm” at Condition One. Note that he is standing, allowing for full 360 degrees of movement freedom.

What I experienced at the Condition One exhibition was clearly a whole new level of audience involvement in subject matter. I don’t see so much of a future in staged, fictional live action VR entertainment, but the documentarian end of things – transporting an audience into a real environment and letting them experience this world up close – is an incredibly powerful opportunity for filmmakers.

EDIT: Animal Equality has uploaded a trailer for the experience, as well as the Factory Farm experience itself. Please note that you ABSOLUTELY should watch it on a VR Headset, as the “real deal” experience is 5-10 times stronger than just using your cursor on a 2-D youtube interface.

-

SIE Magazine9 years ago

SIE Magazine9 years agoWhat Makes A Masterpiece and Blockbuster Work?

-

Filmmakers9 years ago

Filmmakers9 years agoFilms That Changed The World: Philadelphia (1993)

-

Media Impact5 years ago

Media Impact5 years agoCan We Believe The Gillette Ad?

-

SIE Magazine9 years ago

SIE Magazine9 years agoDie Welle and Lesson Plan: A Story Told Two Ways

-

Academia8 years ago

Academia8 years agoFilmmaking Pitfalls in Deal-Making and Distribution

-

Academia8 years ago

Academia8 years agoJoshua Oppenheimer: Why Filmmakers Shouldn’t Chase Impact

-

Filmmakers9 years ago

Filmmakers9 years agoStephen Hawking vs The Elephant Man

-

Academia9 years ago

Academia9 years agoIMAX Documentaries: Exploring Our 7th Sense