Academia

The Camera Has Ears

When film transitioned to sync sound in the late 1920s, practitioners faced the question of sound perspective. Specifically, when recording sound on set, where should the reference for volume level be located in the filmic world? What we would call sound mixing in post-production today, and what they often referred to as dubbing and/or duping, was in its crude infancy. As a result, this audio issue became largely one for production to resolve.

One school of thought strongly believed that the camera should be the reference point for sound. There is a certain logic to this. The audience sees as if they were placed as the camera. Shouldn’t a film’s sound come from the same vantage point?

Sound recordist Edward Bernds told a story of how in 1928 United Artists brought in Dr. J. P. Maxfield, a Ph.D. in Architecture with a specialty in acoustics, to run some recording tests for them. While talking with director Roland West on set, Maxfield was appalled to discover that microphones were then placed above the actors’ heads, as close to the performers as the camera line would permit. Maxfield thought that this was all wrong, as he believed:

The ears of the audience were not above the actors. Their ears — the microphones — should be where their eyes-— the cameras — were. Roland West welcomed that idea. He told Maxfield that he stood beside the cameras and was able to hear every word spoken by his actors. Maxfield was triumphant, his theory was vindicated. He was so enthusiastic that the UA studio heads asked him to make a test, and one was arranged, with hired actors and a full camera crew.

For this shoot, Maxfield created a visual reminder for the crew:

Maxfield set up his microphones, two of them — “two ears,” he said — and placed them close to the camera booth. To complete his setup, he fastened them to a medicine ball, to simulate a man’s head.

As a practical and experienced film practitioner, Bernds saw the flaw in Maxfield’s logic that the camera had ears. Camera placement does not always determine image size and thus serves as a poor reference point for audio. Bernds wrote:

Maxfield’s idea ignored one important fact. The cameras, his “eyes,” might not move, but the lenses could be changed. With a 75mm lens, a camera, from a distance of about twelve feet, could get an excellent close-up of an actor’s teeth, if he smiled and if he had teeth. With a 50mm lens, the actor would be seen in a nicely composed medium close-up. With an 18mm lens he would be a distant figure. The camera people didn’t mention the lens change problem. They probably wished so fervently for relief from the obnoxious overhead mics that they hoped, somehow, that Maxfield’s theories could be implemented. When the test was run, the next day, it was a disaster. Even when the actors faced the camera their voices were weak and indistinct; when they turned away, their voices had a distant, voice-in-a-barreI quality. The embarrassing test film was quietly taken out of circulation, and Maxfield was seen no more.

Maxfield did not disappear immediately, and the debate on sound perspective continued. Rick Altman reports that engineers of this transitional era broke into two camps — one of RKO and the other AT&T engineers. By the early 1930s, however, Maxfield with his philosophy that the camera has ears had lost the argument. By then, techniques associated with modern post-production, namely sound mixing, became more sophisticated, and changes in sound levels could be more successfully performed after production. Practitioners stressed the need for clean and strong sound recording during production rather than setting volume levels then. They found that this sound could be more successfully manipulated in post-production. To record the cleanest sound, practitioners increasingly sought proximity to actors as they experimented with overhanging mics, boom mics, multiple mic set-ups, hidden stationary mics, and lavalier mics.

The general rule today with sound perspective with regard to dialogue is twofold. First, make sure the dialogue is intelligible and clear. Second, sound in dialogue works best when the characters are in close-up or medium shot. Even as Maxfield’s concept of the camera with ears was invalidated, the dialogue volume still seems to bear some relationship to the apparent (though not actual) camera placement —specifically, to image size in the frame. Editor Evan Schiff estimates that over 95% of the time dialogue occurs with a close-up or medium shot shown. According to Schiff, the rare occasions where this rule is broken tend to be at the very start, a moment in the middle, or at the end of scenes where audible dialogue is not the primary and dominant sound.

There are noted stylistic moments that don’t follow this rule, of course. Interestingly, they are few enough that they do stand out. One is the famed walking scene in Annie Hall (1977), where Woody Allen and Tony Roberts walk down the street bantering. At first, they appear far in the distance, an impossible distance to be clearly heard from the camera’s apparent location and yet they are. As they approach and keep talking, the volume level doesn’t change. The scene remains a stellar cinematic moment and a remarkably uncommon one.

Early sound film did indeed struggle in general with the concept of sound perspective as practitioner and audience alike adjusted to audio that came from speakers instead of from musicians in the room. For example, in the 1929 Studio Murder Mystery, two characters converse inside of a room with the camera placed outside the window. We hear them reasonably clearly from there, which today could be considered a very stylistic turn. The reviewer in the June 10th, 1929 NY Times felt otherwise:

Director Frank Tuttle depicts a woman and a girl at a window and although the window is raised about six inches, no thought is given to the fact that the voices ought to be more modulated because they are coming from the other side of what is at least presumed to be a glass interference.

For the reviewer, the sound perspective made no sense. Today, most films simply avoid this problem by choosing to show close-ups and medium shots when characters speak, so it does seem that the camera might actually have ears. Perhaps Maxfield was right after all.

Works Cited

Altman, Rick. “Sound Space.” Sound Theory, Sound Practice. Ed. Rick Altman. New York: Routledge, 1992. 46-64.

Bernds, Edward. Mr. Bernds Goes to Hollywood: My Early Life and Career in Sound Recording at Columbia with Frank Capra and Others. Lanham Md; London: The Scarecrow Press, 1999.

Annie Hall. Dir. Allen, Woody, MGM Home Entertainment Inc. MGM Home Entertainment, 2011.

Schiff, Evan. Interview. June 5th, 2015.

The Studio Murder Mystery. Dir. Tuttle, Frank. 1929.

Academia

What is USC’ Media Institute for Social Change?

The Media Institute for Social Change, known as MISC, is a production and research institute at the USC School of Cinematic Arts focused on using media as a tool for effecting social change. Founded in 2013 by Michael Taylor, a producer and Professor in the School’s famed Film & Television Production Division, the MISC maxim is that “entertainment can change the world.” It spreads this message by producing illustrative content, and by mentoring student projects, awarding scholarships and leading research. “We are training the next generation of filmmakers to weave social issues into their films, television shows and video games,” says Taylor. “As creators the work we do has a huge impact on our culture and that gives us an opportunity to influence good outcomes.”

In recent years MISC has partnered with organizations including Save the Children, National Institutes of Health and Operation Gratitude, and creative companies like Giorgio Armani, the Motion Picture Association of America and FilmAid, to create groundbreaking work that have important social issues woven into the narrative. MISC also worked with USC’s Keck School of Medicine to create Big Data: Biomedicine a film that shows how crucial big data has become to creating breakthroughs in the medical world. Other MISC films include the upcoming The Interpreter, a short film centered on an Afghan interpreter who is hunted by the Taliban, and The Pamoja Project, the story of 3 Tanzanian women who determined to help their communities by immersing themselves in the worlds of microfinance, health and education. MISC has also partnered with the app KWIPPIT to create emojis that spread social messages. Together they co-hosted the Project Hope L.A. Benefit Concert to spread awareness about the massive uptick of homelessness in Los Angeles.

The Power of the PSA or How to Change the World in 30 Seconds, which documented the institute’s collaboration with the Los Angeles CBS affiliate KCAL9 to make PSAs on gun violence, internet safety, and PTSD among veterans. Another MISC-sponsored film, Lalo’s House, was shot in Haiti with the intention of exposing the child trafficking that is rampant there and in other countries, including the United States. The short film (which is being made into a feature) was used by UNICEF to encourage stricter legislation prohibiting the exploitation of minors, and has won several awards, including a Student Academy Award.

“Our goal,” says Taylor, “is to send our students into the industry with the skills and desire to make entertainment that has positive impact on our culture.” The dream is a variety of mass-media entertainment where social messages aren’t an afterthought but are central to the storytelling.

For more about MISC and its projects, go to uscmisc.org.

Media Impact

Can We Believe The Gillette Ad?

The new Gillette Ad. It’s Pepsi #2. It’s poorly executed, laden with half-hearted strategy, an elephant in the China shop of gender relations.

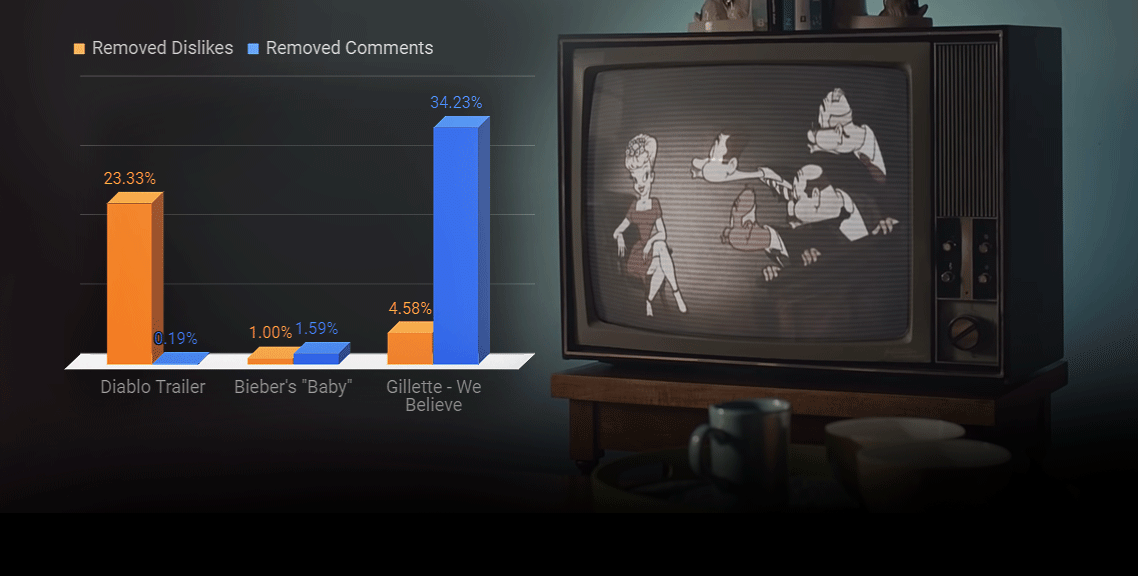

Numerically speaking, it’s not what it seems to be either. 34% of the ad’s comments were deleted, far more than other videos in similar dislike territories. Gillette’s account might just have set the YouTube proportional record for deleting comments on a single video (the absolute record goes to YT’s own Rewind 2018).

Taking Count – What Numbers Are Real on YouTube?

There have been repeated claims, mostly by YouTube commentators, that dislikes and comments were deleted. Another claim group was that the proportion of likes to dislikes seemed manipulated since it changed from a 10:1 ratio to a 2:1 ratio within days. Some outlets picked up the story, but nobody dove much deeper than a few screenshots. Well, after a few days and 3.000+ measurements we have answers for you.

With the help of YouTube’s API and Archive.fo’s screenshots of the video’s public numbers, we were able to test the claims of whether Gillette’s dislike and comment count were being subject to unusual moderator deletion.

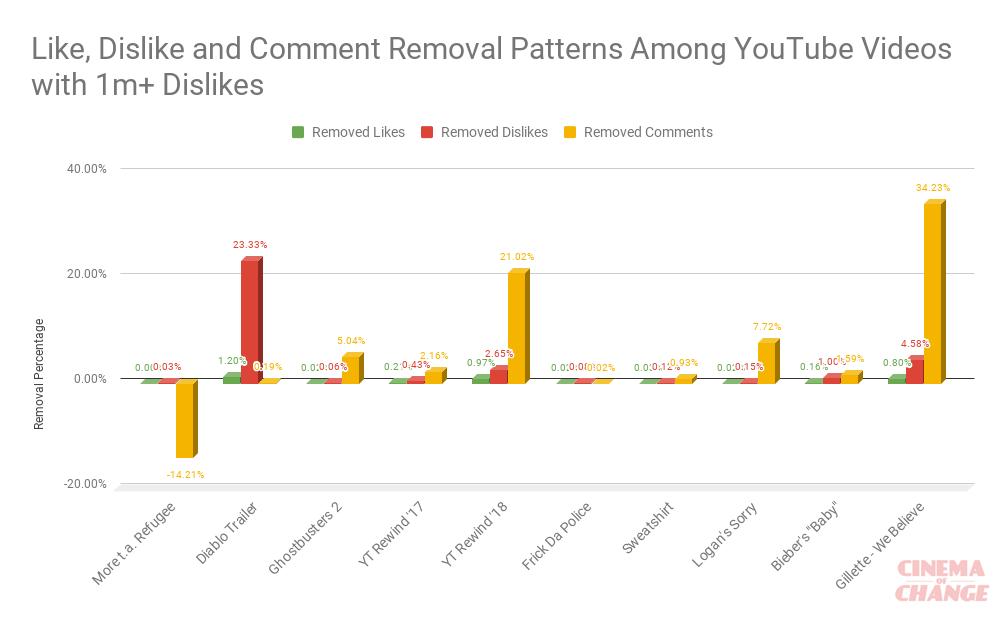

Before we ask that though, it’s important to know how much moderation usually goes on in other controversial videos. If it’s common to delete a certain amount of comments/dislikes, then the criticism of Gillette isn’t directly fair – it’d just be part of the YouTube ecosystem. To get a litmus test of “how common is comment/dislike moderation in similarly controversial videos”, we used a few close neighbors in the List of most disliked YouTube videos as comparables and measured the front-end/back-end discrepancy.

One of them was a “Diablo” game trailer that also received criticism that the publisher had deleted comments and dislikes. Our research was simple – we made API queries to YouTube’s server back-end over the course of a few days while manually transcribing screenshots of the front-end from Archive.fo for similar time spans. While YouTube’s server keeps all video interactions on record, even fraudulent or bot-based ones, the public front-end is influenced by a filtering mechanism that hides certain interactions.

Claim 1: The Gillette Ad Had A Manipulated Growth Pattern

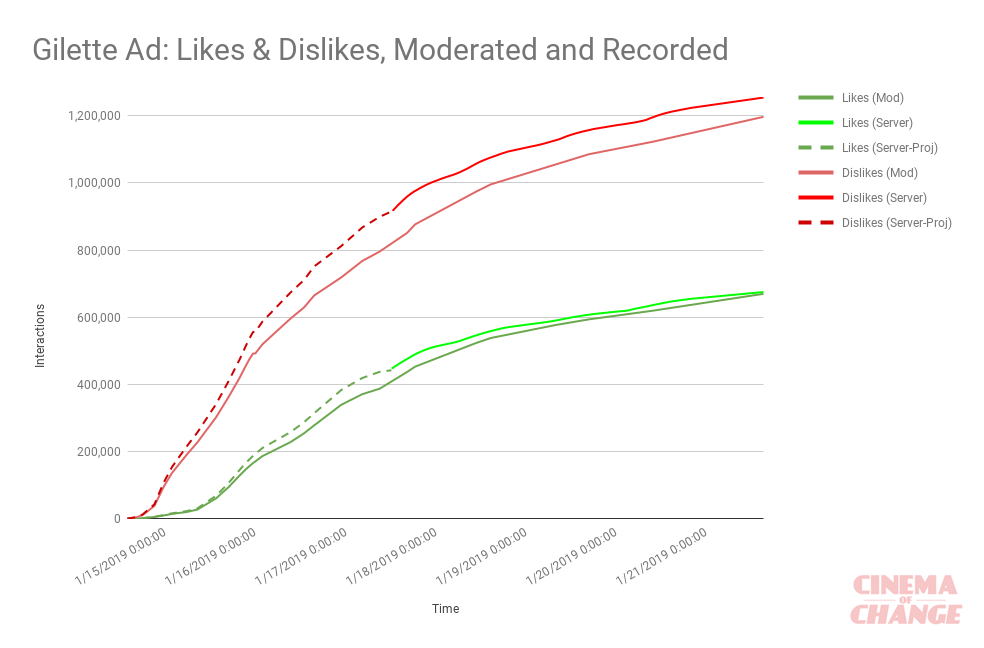

There was nothing really unusual about the growth pattern of likes and dislikes in the Gillette video while we were measuring it. But we started measuring server data on Day 3 of the video being public – the first 3 days we only know from public screenshots, and can project how the deletion pattern must have created a difference.

The growth and change of server-side as well as public facing likes and dislikes on the Gillette “We Believe” ad on YouTube.

You can see that in the beginning, dislikes took off very quickly, while likes had a slower growth, but eventually the growth rates approximately equalized, so now there’s a constant 500k lead on dislikes to likes. This is a simple explanation for the changing ratio from 10:1 to 2:1, and we have reason to believe there was no foul play at work there.

Interestingly enough, while there are more dislikes than likes that were hidden by moderators, the likes count disparity shrinks as time goes on, essentially un-hiding likes again. This might be a technical glitch, since a similar shrinkage of hidden dislikes seems to be going on as well.

The archival data only records public likes and dislikes, not comments – so we aren’t sure about the comment deletion pattern over time.

Like data? Take a look at the public spreadsheet.

Claim 2: A High Number of Dislikes and Comments Were Deleted

What was far more surprising to see was the comparison to other highly disliked videos. The server queries resulted in two real outliers – Diablo’s massive deletion of dislikes, and Gillette’s outstanding number of comment deletions. While Blizzard eradicated 220k dislikes on its Diablo Immortal trailer (that’s 23% of the total) from public view (Gillette only deleted 5%, slightly above average), Gillette deleted a whopping 34% of its comments – 172,000 comments to be precise. This is closely followed by YouTube’s own 2018 Rewind video, which has 21% of its comments removed and is the most-disliked video in YouTube history.

Gillette deleted a potentially historic fraction, 34%, of its comments on the “We Believe” video. Blizzard removed 220,000 dislikes on its worst received game trailer, and YouTube banned 21% of the comments on the latest Rewind video.

Here’s the underlying spreadsheet for that data.

There’s a reasonable argument that the comments on Gillette’s ad were so hateful that they had to be deleted, and the primary fuel to that fire would be the implicit attack on men in general, or the explicitly feminist message. The argument is solid when examining anti-feminist culture on YouTube; Feminist Frequency has their comments and likes disabled since the Gamergate controversy (also on server side), the most-watched pro-Feminist video is a TED Talk and has about 3,000/15% of comments deleted. Then again, semi-viral videos that would fit the “men will feel uncomfortable” category, like the Billie Bodyhair campaign or 10 hours of walking in NYC as a woman or #ustoo PSA, don’t have strong deletion patterns (approx. 1-2%).

If we want to know why Gillette proportionally deleted more comments than anyone else in that league, there’s only one way to know: For Gillette to give the public some insights in what their deletion policies looked like.

Note 1: “More than a Refugee” somehow has more comments publicly displayed than the server-side API query counted – I’m not sure how that’s even technologically possible.

Note 2: After talking with a number of large-channel YouTube managers, I was told that it was not possible to delete dislikes. Well – Blizzard’s 20% dislike deletion shows that YouTube makes exceptions.

Not Just Numbers – Let’s Talk Impact

After analyzing the numbers on YouTube engagements, the question to ask is: How did this happen? Why was the blowback so severe? Gillette was in a unique position to turn the gender relations conversation into a very engaging campaign that would have mobilized people positively. But they didn’t. Instead of focusing on progress, they focused on ambiguous, polarizing messaging.

In short, the “We Believe” ad was a waste of Gillette’s potential. And here is why.

I am all for purpose-driven marketing. I spend day and night thinking about and actually producing impact-driven content. And when that kind of advertising is done right by big agencies, it’s really quite incredible to watch positive impact unfold.

Well-Executed Campaigns as Primers

Take the Kaepernick ad by Nike. It asks people to dare to “dream crazy”, and took a political stance against the oppression of black people in the U.S by featuring Colin. That gamble played out well; the backlash was outweighed by support, and the market responded positively for a good run.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fq2CvmgoO7I

.

Or remember the Winter Olympics ad, “Proud Sponsor of Moms”? Guess who did that. P&G, parent company of Gillette. Everyone loved that. And in case you don’t watch much advertising, they did more of those, with bold themes and increasingly diverse casting.

P&G followed it up by tastefully celebrating black people’s identity and appearance with “Dear Black Man”:

.

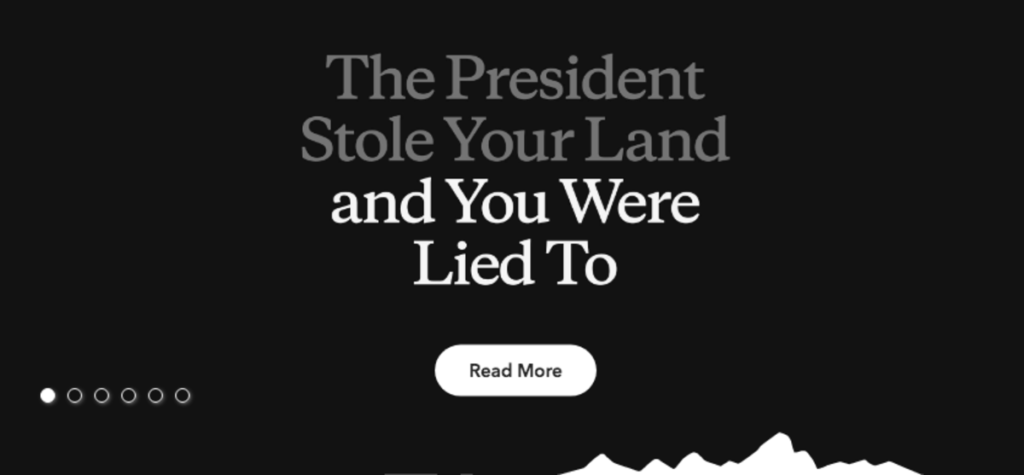

Patagonia didn’t even use a video – they just turned their website dark and said “The President Stole Your Land” as a response to Trump’s threatened shrinkage of National Parks, and then sued him. The market liked it.

There are countless other examples of brands choosing more aware, purpose-driven marketing campaigns.

Watch at least a few of those above to get a primer of “what works”.

What all of them have in common is that they picked an impact area that was either agreeable to most their viewers, or close enough to their company ethos that controversy wouldn’t erode their loyal, primary customer base.

How Not to Do It: Gillette Ad & Pepsi Ad

Now compare this with the below:

Pepsi – “Jump In”:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dA5Yq1DLSmQ

Gillette – “We Believe: The Best Men Can Be”:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=koPmuEyP3a0

.

Pepsi co-opted a social movement with a reality TV character and then preached unity when the world looked starkly divided. And even though some Pepsi drinkers might also watch the Kardashians, they saw through the half-hearted charade: Pepsi had nothing to do with activism, period. It was an “out of the blue” decision to capitalize on something happening in the world, and it felt fabricated.

Gillette did the same. Gillette has nothing to do with feminism, or with anti-bullying. Someone at Gillette decided to make this a cause out of the blue.

Gillette co-opted legitimate movements and issues like #metoo, but instead of sheepishly celebrating a soda version of a harsher reality like Pepsi did, it opened with s bad apples as representatives of its core base without delineation, and then sprinkled in a sugar coat of suggestions for all men on how to be better. Nothing new there, it’s just political now.

As a reality check, “toxic masculinity” is a pretty confusing nomer for negative aspects of masculinity. A Gillette ad for women opening with “Abusive women” wouldn’t work just like a US Army ad opening with “Un-patriotic Americans”. The conflation of two words creates ambiguity outside of an academic debate – is the adjective-noun pair describing the quality of the noun, or is it referring to a sub-part of the noun that matches the adjective? To further go into a grey zone, the “toxic” voice over is largely drowned out by “harassment” in the ad, resulting in a “sexual harrassment masculinity” sound upon first listen.

We’re not on a college campus dissecting word pairs here – we are in the world of impact-driven advertising to mass audiences, and you can’t afford ambiguity in this arena. Anyone that looks past these sloppy linguistic choices is providing Gillette a biased playing field.

.

The rest of the video is full of caricatures of bad men mixed with normal men, and an eventual return to “being the best”.

But by then, the base has tuned out, and Gillette has lost. Not only many of their customers, but an opportunity: To actually reshape and contribute to masculinity. To actually make an ad that men will watch, will love, will share, and will actually make them better men. An ad that all men can agree with, without reservations. An ad that doesn’t open with bad apples as representatives. An ad that encourages men to be present in their boys’ lives. A campaign against bullying.

Something that every man can stand behind, and a standard that we’re all proud to live up to. But that chance was wasted for something phony.

Gillette’s skin-tight ads in 2011 remind us of what the brand used to think about women – and how it appealed to similar sentiments it now criticizes, without acknowledging the hypocrisy.

Looking Inward and Forward to Do Better

Why do so few see the charade here?

Gillette could have acknowledged its treatment of women for the past 100 years and apologized, if they wanted to. Nobody really seems to see the irony in applauding to the feminism of the ad and Gillette’s unacknowledged past in contrast.

How about something as complicated as implicit biases by men (like what the boardroom scene tried to address)? Well, they could have done a boy’s version of their Always Ad #LikeAGirl (it’s a bit clunky but the idea is highly effective, and I’m sure it’d have worked with boys too).

All these topics take time and care to implement in separate campaigns. Gillette’s current ad is the impact equivalent of a “YouTube Rewind”, and is heading into similar mashup-dislike-count territory. There have been prior (Harry’s) and later (Egard) attempts to make “men’s issues” themed feel-good ads, but nothing comes close to the “primer” ads on the top, which had an impact edge to them.

A new Adweek Article suggests that the ad was primarily meant for women in the first place, to change their perception of shaving from “disgust” to “joy”. It’s a bit questionable to criticize men as a vehicle to position the brand better for women.

Doing ads that honestly criticize without alienating – that is hard. To Gillette’s credit, they at least failed at something challenging – and that is brave.

Non-Profit Tie-Ins Need Care, Not Just Cash

To finish on a slightly hopeful note – it’s wonderful that Gillette decided to donate $1M to the Boys & Girls Clubs of America. Awesome. But that’s all that Gillette had to say on their new thebestmencanbe.org website. No roll-out, no strategy, no content, no pipeline – just a promise of money and a single link to a great nonprofit. That’s the laziest impact follow-through effort I’ve seen in a long time. Sloppy ad, good nonprofit choice, obvious lack of involvement in the actual impact.

Gillette is a big company, and they can absorb a blow. 1.1M dislikes on YouTube isn’t even close to what Justin Bieber gets. But unlike Gillette, Bieber’s team left the negative comments rather untouched.

.

In the world of purpose-driven advertising, I like to hold companies, agencies and decision-makers to higher standards. Not a peer-pressured applause for intentions, but well-earned respect for nuanced execution and actual impact.

Because we all can be better.

And Gillette should be the best they can be.

Companies

Aging and Nuclear War in the Writers’ Room

Have you ever heard of Hollywood, Health, & Society? Most likely not.

Yet, you have probably watched something that they have worked on. With over 1,100 aired storylines from 2012-2017 including those for Grey’s Anatomy, NCIS, and black-ish, Hollywood, Health, & Society (HH&S) serves to provide entertainment industry writers with accurate information on storylines related to health, safety, and national security. This pretty much includes everything from aging to nuclear war.

For example, that April 30th, 2017, episode of American Crime that included immigration, opiate abuse, and human trafficking in the plot? Data analysis is currently in progress for a cross-sectional study of viewers.

With the USC Annenberg Norman Lear Center, HH&S not only pairs experts with writers, but also conducts extensive research on their impact and the correlation between seeing things on screen and audiences’ changed perceptions of those topics. HH&S maintains a low public profile, but is very much involved in the writers’ rooms and guilds. Their approach is two-fold:

1) Reactive – responding to requests and needs for HH&S services, which manifests in the form of phone calls and/or emails to the center, expert consultations, guidance on accurate language.

2) Proactive – introducing writers and entertainment professionals to subject matter experts through panel discussions, screenings and immersive events; a quarterly newsletter, tip sheets and impact studies.

Students, you are welcome to use this resource as well! HH&S serves writers at all stages of their careers, although of course, shows on the air or already in production have priority.

To learn more about the research and impact studies behind HH&S:

– Featured list of tip sheets for writers

– CDC’s list of tip sheets from A-Z

– On location trips for writers to gain understanding for certain topics

Follow Hollywood, Health, and Society on Facebook and Twitter to stay updated with their work and upcoming opportunities.

-

SIE Magazine9 years ago

SIE Magazine9 years agoWhat Makes A Masterpiece and Blockbuster Work?

-

Filmmakers9 years ago

Filmmakers9 years agoFilms That Changed The World: Philadelphia (1993)

-

Companies6 years ago

Companies6 years agoSocial Impact Filmmaking: The How-To

-

Media Impact5 years ago

Media Impact5 years agoCan We Believe The Gillette Ad?

-

SIE Magazine9 years ago

SIE Magazine9 years agoDie Welle and Lesson Plan: A Story Told Two Ways

-

Academia8 years ago

Academia8 years agoFilmmaking Pitfalls in Deal-Making and Distribution

-

Academia8 years ago

Academia8 years agoJoshua Oppenheimer: Why Filmmakers Shouldn’t Chase Impact

-

Filmmakers9 years ago

Filmmakers9 years agoStephen Hawking vs The Elephant Man